The Math of China's Consumer-Led Rebalancing

Quantifying key milestones on the road to rebalancing.

I have long argued that the time has finally come for China to tackle the imperatives of consumer-led rebalancing. The old growth model — led by investment and exports — has been extraordinarily successful in alleviating poverty and raising the overall standard of living for the most populous nation in the world. But a protracted Chinese property crisis and an outbreak of global protectionism have unleashed powerful and enduring headwinds to the hyper growth model of 1981 to 2021, while China’s emerging middle class now seeks a larger slice of the pie.

Chinese rebalancing, of course, has been a subject of active debate for nearly two decades, dating back to 2007 and the “Four Uns” critique of former Premier Wen Jiabao.

There have been countless suggestions of how to accomplish this daunting task. I have long favored social safety net reforms aimed at reducing the excesses of fear-driven precautionary household saving. Others have argued for Hukou reforms to benefits some 300 million migrant workers, increased trade-in campaigns for consumer durables, fiscal reforms, land reforms, and a new urbanization strategy.

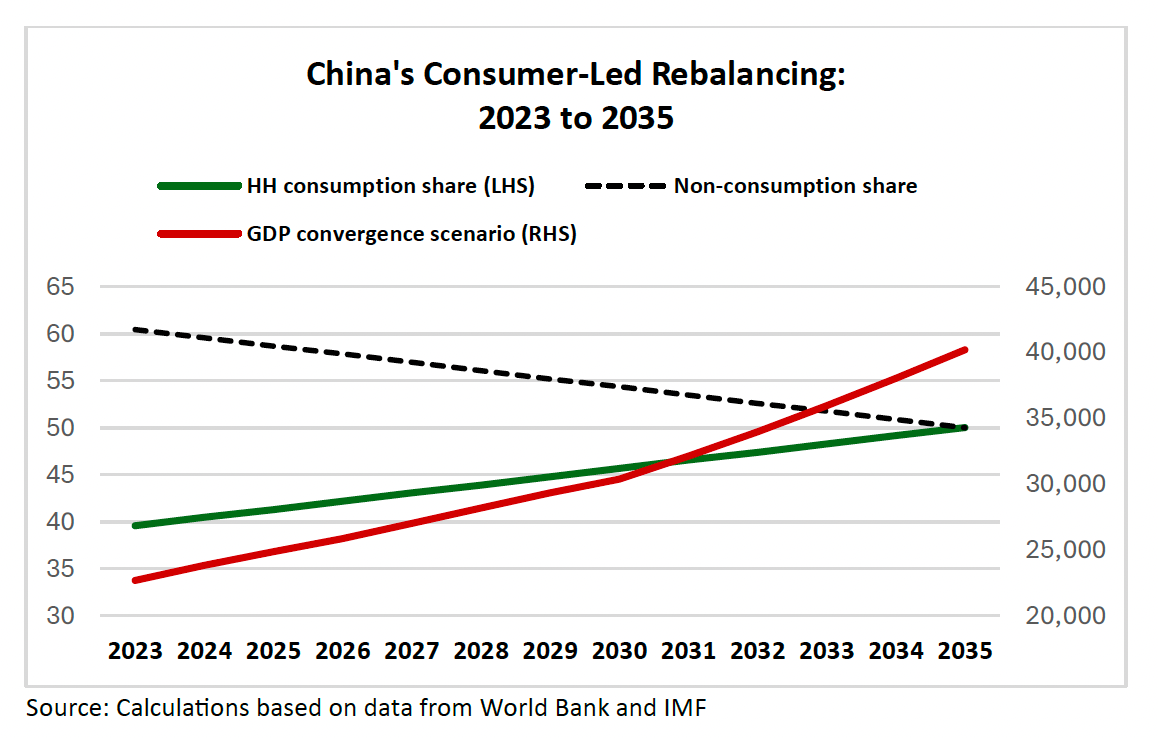

While the debate over China’s consumer-led rebalancing strategy is far from settled — and I don’t propose to do that in this post — it is important to appreciate what such a structural realignment might entail in terms of the shifting mix of the Chinese economy. I recently suggested that the upcoming 15th Five-Year Plan should endorse the specific target of a 50% household consumption share of Chinese GDP by 2035 — a ten-percentage point increase from the 40% share of 2023. Targets offer both discipline and accountability that endless debate and discussion over structural rebalancing cannot provide.

In what follows, I offer more detail on what it would take to hit this 50% consumption target. That requires the decomposition of a baseline projection of Chinese GDP between now (2025) and then (2035). To do that, I have selected a GDP trajectory that is aligned with the “rejuvenation scenario” that I discussed several weeks ago, which depicts a convergence of Chinese per capita output with that of the advanced economies by 2049.

To be sure, this is an optimistic assessment. It is largely consistent with Chinese President Xi Jinping’s long ambitious growth aspirations that have been couched in terms of his commitment to the “Chinese Dream.” Accordingly, it reflects an acceleration to 5.75% per capita GDP growth over the 2030 to 2049 period, well short of the 8.4% average gains during the 40-year hyper growth era of 1981 to 2021, but meaningfully faster than the relatively sluggish 4.3% growth pace projected from 2022-30.

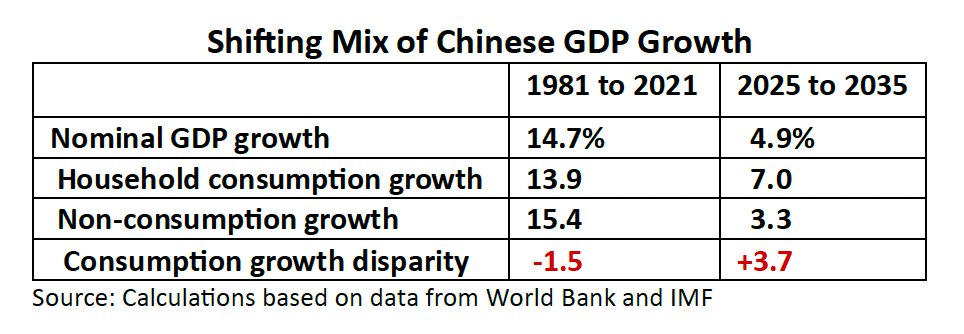

Against the backdrop of this optimistic rejuvenation scenario, I have calculated what that outcome would imply in terms of growth in household consumption and growth for the remainder of the Chinese economy (the “non-consumption “share). Unsurprisingly, this implies considerably faster growth in the now smaller segment of the economy (household consumption) to catch up with the currently much larger investment-led portion in the remainder of the Chinese economy. Under the assumption of steady incremental increases of 0.87 percentage point per year in the household consumption share from 40% in 2023 to 50% in 2035, that translates into 7% average household consumption growth versus 3.3% average growth in non-consumption Chinese GDP over the 2025 to 2035 period.

In one respect, these relative growth calculations are curious: As can be seen in the table below, the projected growth of 7% in household consumption over the next eleven years is well below the 13.9% average annual gains during the 40-year high-growth era of 1981 to 2021. But, of course, the Chinese economy has expanded dramatically over that period; 2021 GDP was more than 235 times what it was back in 1981. Faster growth off a dramatically smaller base is normal for any developing economy before the scale effects kick in and reduce percentage gains. The main point of the consumer led rebalancing scenario, underscored below by the numbers in red, is that the historic investment-led disparity during the hyper growth era will need to be reversed by more than five percentage points over the next eleven years (from -1.5 to +3.7 percentage points).

These numbers are presented less as a forecast and more as an illustration of what the math of Chinese consumer-led rebalancing implies. To me, they make sense for three reasons: One, they underscore the reversal that will be required in the relative growth rates between consumption and the remainder of the Chinese economy. Two, the calculations are consistent with the prognosis of a marked slowdown in fixed investment — especially residential construction — as the main historical driver of modern China’s high-growth economy. Three, while the calculations only go through 2035, a key milestone on the 2049 rejuvenation trajectory, they could well spell the difference between a “good dream” and a “bad dream” in terms of China’s potential convergence with the advanced economies as set out by Xi Jinping.

There are plenty of caveats to these calculations. I have couched the structural shift in terms of a steady 0.87 percentage-point annual increase in the household consumption share of Chinese GDP over the next eleven years; due to policy lags, the gains could conceivably be backloaded — less of an increment in the years immediately ahead and sharper increases in the out-years. Additionally, I make a purposely vague reference to the “non-consumption” share of the Chinese economy; that, of course is dominated by fixed investment which accounts for some 40% of Chinese GDP in 2025, or nearly 70% of non-consumption GDP. While a long-term decline in the crisis-torn residential construction share is likely to lead the compression in overall investment, a potential post-property-crisis offset arising from continued urbanization is possible. Finally, the baseline GDP trajectory may be an overly optimistic assessment of China’s potential for convergence with the advanced economies; however, without consumer-led rebalancing, convergence may well be stymied.

I can live with these caveats. The debate over China’s consumer-led rebalancing strategy has become ponderous, drawn out for far too long. The time for heavy lifting is at hand — the sooner the better. The scenario sketched out above provides some realistic milestones of what to expect on the road to Chinese rebalancing.

There are two ways to raise the consumption share in Chinese GDP. One is to lower the savings rate out of household disposable income. The other is to raise the share of households in national income. Stephen's preference seems to be the former. But I don't think it is plausible that the household savings rate will fall enough for consumption to grow substantially faster than national income over the long term. So, the distribution of income must also be addressed. That is an inescapable policy issue for China if it wants a significantly higher share of consumption in national income. I look forward the Stephen's discussion of these policy issues.