China's Last Structural Paradox

Social safety net reform is key to resolving China's disconnect between rising services and stagnant household consumption.

One of the most enduring paradoxes of the Chinese growth miracle is that the stunning success of the nation’s services sector development has not been matched by comparable increases in household consumption. This is at odds with the characteristics of more advanced economies, where services and consumption shares tend to move closely in tandem. A resolution of this paradox may well hold the key to China’s long-awaited and increasingly urgent consumer-led rebalancing.

My own take on this issue dates back to 2007 and the famous “Four Uns” critique of former Chinese Premier, Wen Jiabao. During a press conference following the conclusion of that year’s National People’s Congress, Wen argued that while topline growth of the Chinese economy was, at the time, strong on the surface, he was concerned about an economic structure that, beneath the surface, was increasingly unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated, and ultimately, unsustainable. This sparked the great Chinese rebalancing debate, which has been ongoing ever since.

China has made considerable progress on the road to rebalancing. It has reduced a massive current account surplus, lowered the energy content of its GDP, increased the connectivity of a rising urbanization through the Internet and high-speed rail, shifted from imported to indigenous innovation, and promoted the development of its services sector. Despite this progress, China has failed to boost the consumption share of its economy. At 39.6% of its GDP in 2023, the household consumption share is only slightly above the 36.6% reading of 2007 — leaving China with the lowest portion of consumer demand in any major economy in the world today.

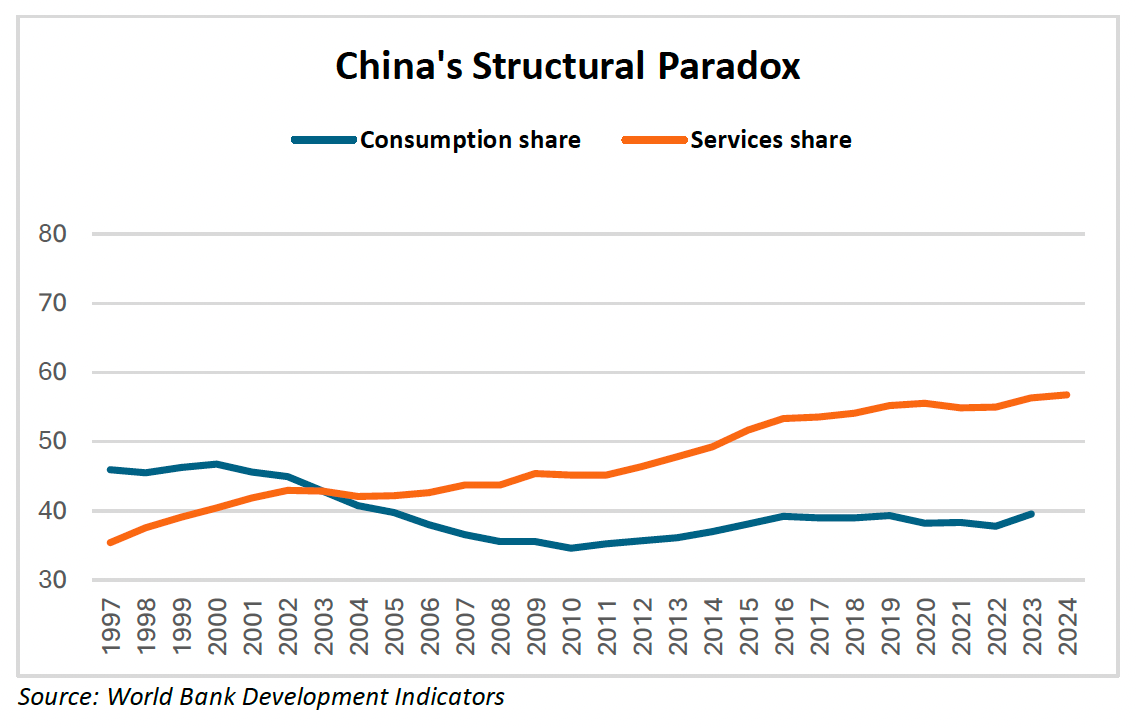

Particularly striking, as can be seen in the first chart below, is that the divergence between the services and consumption shares of Chinese GDP has become more pronounced since Wen Jiabao 2007 observations. The subsequent persistence of a sub-40% household consumption share stands in sharp contrast to a services share that rose from 43.7% in 2007 to 56.7% in 2024. Putting it another way, from 2007 to 2023, the incremental increase in the services share of Chinese GDP (13 percentage points) was more than four times the increase in the consumption share (3 percentage points).

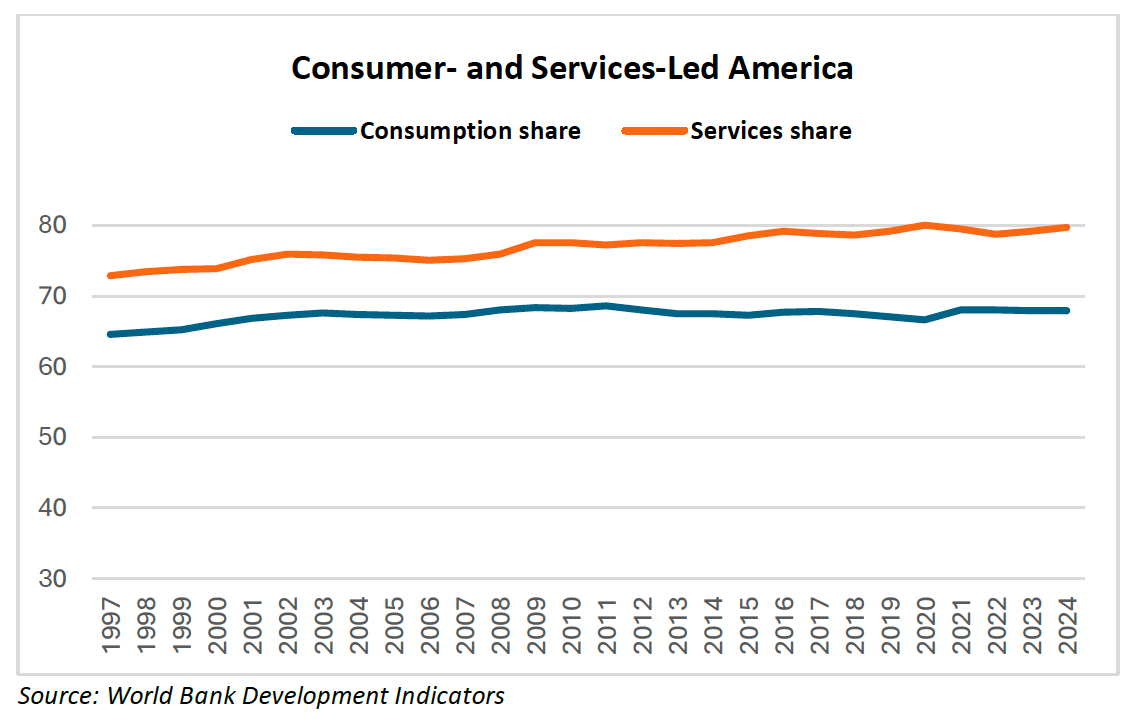

The services-without-consumption phenomenon is not only at odds with the experience of modern, advanced economies — the United States is shown for comparison in the second chart below — but it flies in the face of long-held notions of prosperity and affluence best articulated by John Kenneth Galbraith. For China, this is understandable in one key sense: as a developing nation, saddled with the legacy of an under-developed services sector, China had to start from scratch in putting together the modern trappings of a services-based economy. As such, the initial focus was directed mainly at the building blocks of a services-based infrastructure — wholesale and retail trade, telecommunications, public utilities, transportation, and finance.

Having made great progress in putting this foundation in place, China now has the opportunity to turn to the next phase of services-led development by promoting the growth of professional and personal services. That would include lawyers, doctors, accountants, consultants, scientists, and entertainers, along with the managerial, technical, and support staffs that these occupations require. That poses a big question: Are Chinese living standards high enough to afford this transition to a more affluent society?

By IMF metrics, China’s GDP per capita is estimated to be slightly above $24,800 (PPP-based constant dollars) in 2025; that’s only about 40% of the $63,000 average for the advanced economies. As I discussed recently, per capita output convergence between China and the advanced economies is possible by 2049 — provided that Chinese economic growth picks up from the current sluggish pace; specifically, that would require China’s per capita GDP growth to move back to a 5.75% trajectory, 1.5 percentage points faster than current gains (4.3% from 2022 to 2030) but well short of the 8.4% pace of the high-growth era (1981 to 2021).

The transition from today’s “moderately prosperous society,” as per Xi Jinping’s assessment, to the high-income status envisioned by 2049 will undoubtedly usher in the next phase of services development — the professional and personal services that a more affluent China will then be able to afford. Significantly, this new source of growth will also have the potential to play a key role in boosting discretionary consumption. That reflects the circularity of what economists have long dubbed “Say’s Law,” that increased output on the supply side of the equation — in this case, services — will generate employment and income growth that, in turn, creates more aggregate demand.

This gets to the heart of China’s consumption problem — a nation that has long been stymied by the translation of labor income generation into consumer demand. The main reason: a rapidly ageing society and an inadequate social safety net — a combination that prompts excessive precautionary saving. Fearful of an uncertain future, increasingly older Chinese households are predisposed toward saving over consumption. China’s household sector saving rate currently stands at about 35% of GDP, by far, the highest of any major economy in the world, and more than double the 14% average in developed OECD nations.

I have long stressed the inadequacy of China’s social safety net as the major impediment to consumer-led rebalancing. Over the last fifteen years, China has focused on improving the coverage of its nationwide healthcare and pension plans but has lagged in raising the benefits. As a result, China currently spends a little less that 12% of its GDP on all social welfare programs — not just pensions and healthcare but also unemployment and work-injury insurance as well as childcare support. That is far short of the 21% OECD average.

That underscores the bottom line for resolving China’s consumption paradox: Without more aggressive safety net reforms, China’s consumer-led rebalancing will continue to be hobbled. There has been considerable discussion of this issue for many years. Unfortunately, Beijing has been slow to address the challenge. Hopefully, we will know more about the social safety net prognosis following release of the 15th Five-Year Plan in March 2026. Hints may be available at the upcoming Fourth Plenum in late October.

There are a number of safety net reform proposals that have been floated recently, such as urban-rural (including migrant workers) consolidation of benefits, increased infusion of SOE dividends into the social welfare system, and further increases in the retirement age — just to name a few. My own preference would be to wrap any specific safety net proposals around a broader goal-setting target of a 50% household consumption share of GDP by 2035 — up dramatically from the latest reading of around 40%. Like the 2049 per capita output convergence scenario discussed above, targets add an important element of accountability and policy discipline that every nation needs, including China. Its central planning legacy and subsequent five-year planning exercises make macro targeting all the more acceptable in China.

In the end, there is no dark secret about the building blocks of consumer demand. At the macro level, there are three legs to the stool — jobs, real wages, and the saving propensity of households. China has been very successful on two of those counts — services-led job creation and urbanization-led increases in real wages. Services are inherently labor-intensive endeavors, and urban workers are paid more than double their rural counterparts. The combination of sustained employment growth and rising real wages provides a strong impetus to growth in labor income. But without a more secure social safety net, the incremental income growth will continue to be saved, inhibiting the growth of discretionary consumption — especially for high-end services — and preventing an increase in the consumption share of Chinese GDP.

The growth problem that Wen Jiabao presciently pointed out in 2007 is now at hand. I am less concerned about the property crisis and debt-intensive growth — both of which are now being addressed by Chinese policy authorities — and more worried about lingering structural problems. The likelihood of ongoing pressures to the global trade cycle draws China’s export-led mercantilist growth model into sharp question. And there can be no arresting the demographic headwinds of a rapidly ageing Chinese society that make social safety net reforms all the more urgent. Service sector development is paving the way. It is high time for Chinese policymakers to step up and deliver on consumer-led rebalancing. Only then can China resolve its last structural growth paradox.