China's Rejuvenation Deficit

A dramatic change in Xi Jinping's political calculus

An “unstoppable rejuvenation,” proclaimed Chinese President Xi Jinping at the recent meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Followed shortly by a massive military parade in Beijing commemorating the end of World War II, there can be no mistaking the geostrategic implications of Xi’s rejuvenation gambit.

It wasn’t always that way. In November 2012, shortly after having been appointed General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi Jinping framed rejuvenation in a very different fashion. It was depicted as key to his peoples-centric vision of the “Chinese Dream,” which stressed “a great renewal of the Chinese nation” as “incessantly bring(ing) benefits to the people.” Over subsequent years, in a series of speeches and pronouncements, Xi tied the rejuvenation construct closely to aspirational economic targets. It was expressed as the means to a moderately well-off society that would raise Chinese living standards to parity with other high-income, advanced nations by 2049, hardly by coincidence, the centennial anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

That put the onus to rejuvenation squarely on the performance of the once high-flying Chinese economy. As long as rapid growth could be sustained, went the argument, the benefits of rejuvenation would, indeed, eventually accrue to the Chinese people. But this was a conditional guarantee of rejuvenation, wholly dependent on the performance of the economy. That proved to be a major complication. The significant slowing of Chinese economic growth over the past decade poses the possibility of a broken promise, giving rise to what can be called a “rejuvenation deficit” — a growth shortfall that requires a major rethinking of the promises of the Chinese Dream.

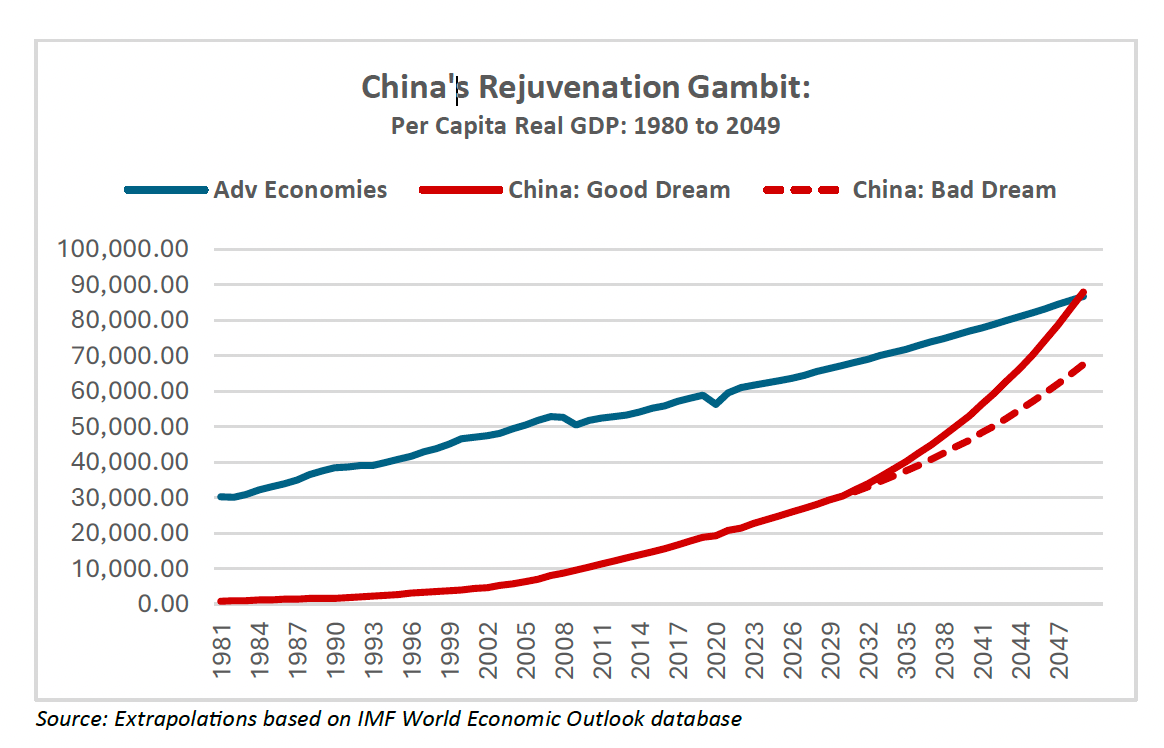

As shown in the chart below, it is possible to put some numbers on the magnitude of the rejuvenation deficit. In doing so, I examine the trajectory of possible convergence between China and the advanced economies through the lens of per capita output — a peoples-based metric very much aligned with XI’s initial interpretation of the Chinese Dream. Currently (2025), as per International Monetary Fund statistics, Chinese per capita GDP is $24,834 (in PPP-adjusted constant prices). That’s about 40% of the average per capita GDP of nearly $63,000 in the broad collection of advanced economies. Notwithstanding today’s outsize disparity, convergence could, in fact, occur by 2049 if Chinese per capita GDP were to expand by 5.75% per annum over the 2030-49 period, more than four times the relatively sluggish 1.35% growth pace that I extrapolate for the advanced economies.

Anything is possible, of course, in the realm of long-term economic projections, and that is certainly the case in the numbers presented above. I base these calculations on hard data from 1980 to 2024, in conjunction with the latest medium-term IMF forecasts from 2025 to 2030. For 2030 to 2049, I extrapolate the sluggish five-year growth prognosis of 1.35% for the advanced economies from 2025 to 2030 indefinitely into the 20-year future through 2049. For China, the 5.75% figure should be thought of as less of a forecast and more of a solution to the convergence problem I posed above: What would it take for China to achieve per capita GDP parity with the advanced economies by 2049?

China’s 5.75% growth solution to the convergence promise of the original Chinese Dream needs to be considered very carefully. First, it is within the realm of China’s recent experience; a 5.75% growth trajectory would be slightly below the 6.3% midpoint of the high growth era (8.4% per annum in per capita terms from 1981 to 2021) and the more recent sluggish trend (4.3% per annum from 2022 to 2030). Second, a 5.75% growth result would, nevertheless, represent a major reacceleration from the post-2021 sluggishness; it would be 1.5 percentage points faster than average gains of 4.3% projected over the 2022-30 interval. Third, the 20-year 5.75% trajectory would represent an even sharper acceleration from the markedly weaker 3.8% growth projections that IMF currently has for 2029-30, the final two years of its medium-term forecast.

A final consequence of this exercise bears special emphasis. By comparing the difference between the two Chinese growth scenarios — the 5.75% convergence trajectory versus the 4.3% extrapolation of recent experience — we can provide a rough approximation of the rejuvenation deficit. This can be thought of as the difference between the Xi Jinping’s original depiction of the Chinese Dream (the convergence of the “Good” Dream) and an outcome that leaves the Chinese economy mired in its current sluggish state (the “Bad” Dream). The difference, courtesy of the powerful math of compound growth, is a big number. If the current rate of sluggish economic growth persists, by 2049, the rejuvenation deficit would amount to slightly more than $20 trillion (in real PPP terms), or approximately 23% of convergence GDP.

I and others have written endlessly about the great Chinese growth debate. Yes, there are plenty of risks on the downside — including debt, property, demography and other Japanese-like concerns — that could give rise to a much larger rejuvenation deficit. But there are also major possibilities to consider on the upside — especially technology (including AI supremacy), advanced manufacturing, and the ultimate benefits of a consumer-led rebalancing — that could shrink the shortfall. While this is not the place to reopen this contentious debate, I reiterate my long-standing view that the Chinese economy is likely to face stiff headwinds in the years ahead. That puts me in the camp that worries about the very real possibility of a seemingly chronic rejuvenation deficit, meaning that it will be exceedingly difficult to validate the Chinese Dream on the peoples-centric terms that were originally presented by Xi Jinping in late 2012.

Like all powerful leaders, Xi Jinping does not want to be wrong. That’s true even in a one-Party state with its own unique strain of political imperatives. The rejuvenation promises of the Chinese Dream are Xi’s legacy bet — one way or another. That’s why Xi’s latest statements and actions are so important. By framing rejuvenation more in militaristic terms, complete with a very public display of China’s modern weaponry and support from barbaric allies like Vladamir Putin and Kim Jong Un, Xi may well be conceding his political losses on economic terms. China’s rejuvenation deficit appears to have turned the political calculus of Xi Jinping inside out.

curious what is the population figure IMF project to calculate 2049 per capita GDP

5.75 pa for 20 years from an economy this size is large; would falling short of that really be a failing? Given the development which has already occurred, that is, given the starting point of today, wouldn’t, say, 2-3x developed economies be a good result?