The Inevitability of Chinese Innovation

A framework-based assessment of the Sino-American battle for innovation and AI supremacy

There’s not a day that goes by when there isn't another breathless story about AI and the threat China poses in dominating this revolutionary breakthrough. Call me dense, but I must confess to having a hard time figuring out why the world is so aghast over China’s apparent prowess as America’s peer competitor in artificial intelligence. After all, from paper to gunpowder, from magnetic polarity and navigational guidance, and with a legacy of far too many other breakthroughs to mention, China was the world’s preeminent innovator from ancient times through the 17th century.

After stalling out during and immediately after the Industrial Revolution for a variety of reasons, detailed in the so-called Needham Puzzle, China has more than made up for lost time. Competitive leapfrogging has become the norm for modern, post-Mao, China. From high-speed rail to telecommunications, from quantum computing and alternative energy, China has been quick to match established leaders on the frontier of technology in terms of scale, quality, and creativity. AI and other leading-edge technologies may well be only the latest installment in China’s long history of scientific discovery and invention, core elements of a rich culture of innovation.

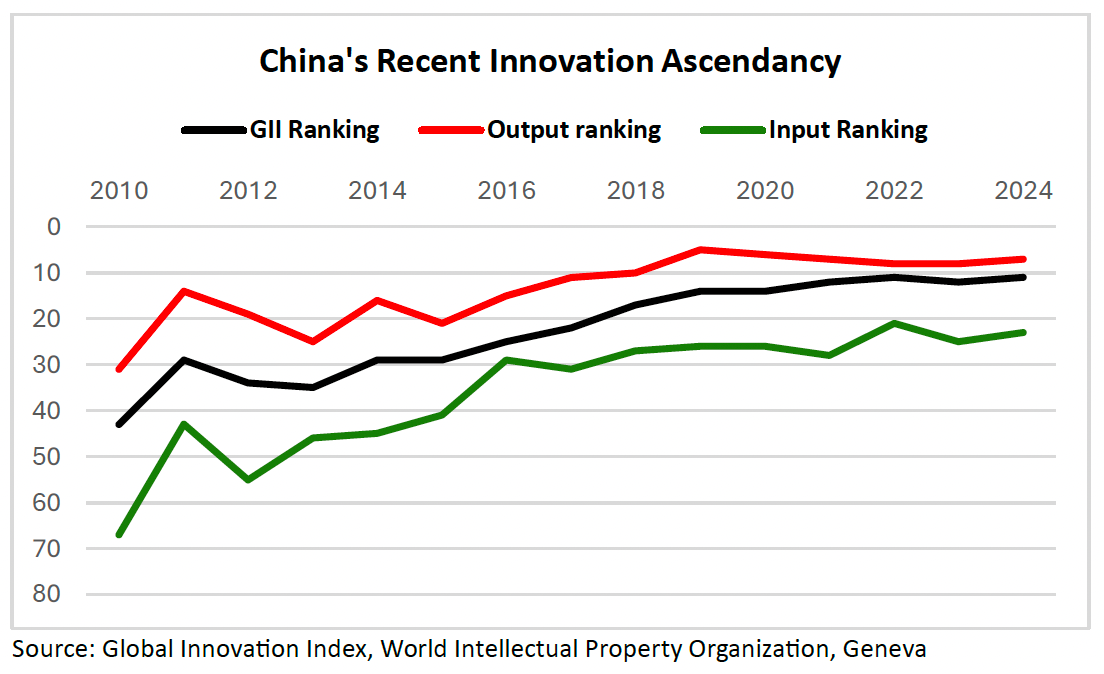

The real surprise is that a complacent West didn’t see this coming. Recent trends in the Global Innovation Index, a detailed compilation of the metrics of innovation for a large sample that now includes some 133 countries, attests to China’s extraordinary progress as a global innovator since 2010. As can be seen in the chart below, in the relatively short span of 15 years, China’s global ranking has moved up from 43rd place (2010) to 11th place (2024). Putting this recent ascendancy in relative terms, China’s competitive innovation disparity with the United States has narrowed dramatically; in 2010, there were some 32 countries separating the two in the GII tally, whereas by 2024, the gap had narrowed to just 8 positions.

The devil is in the detail. Initially launched in 2007 by academics at INSEAD and now assembled under the auspices of the Geneva-based World Intellectual Property Organization, the GII is comprehensive gauge based on 53 indicators of innovations inputs grouped into five functional categories — institutions, human capital and research, infrastructure, market sophistication, and business sophistication — in conjunction with 25 indicators of innovations output organized into two functional categories — knowledge and technology, and creativity output. As can be seen in the chart, since 2010, China’s leadership in innovations output has far outstripped its performance of innovations input; that underscores the relative efficiency of its innovations push —stronger results on the output side than on the input side of innovations equation. In other words, by squeezing more innovations output from the input-based building blocks of innovations, China appears to be benefiting from increased innovations productivity.

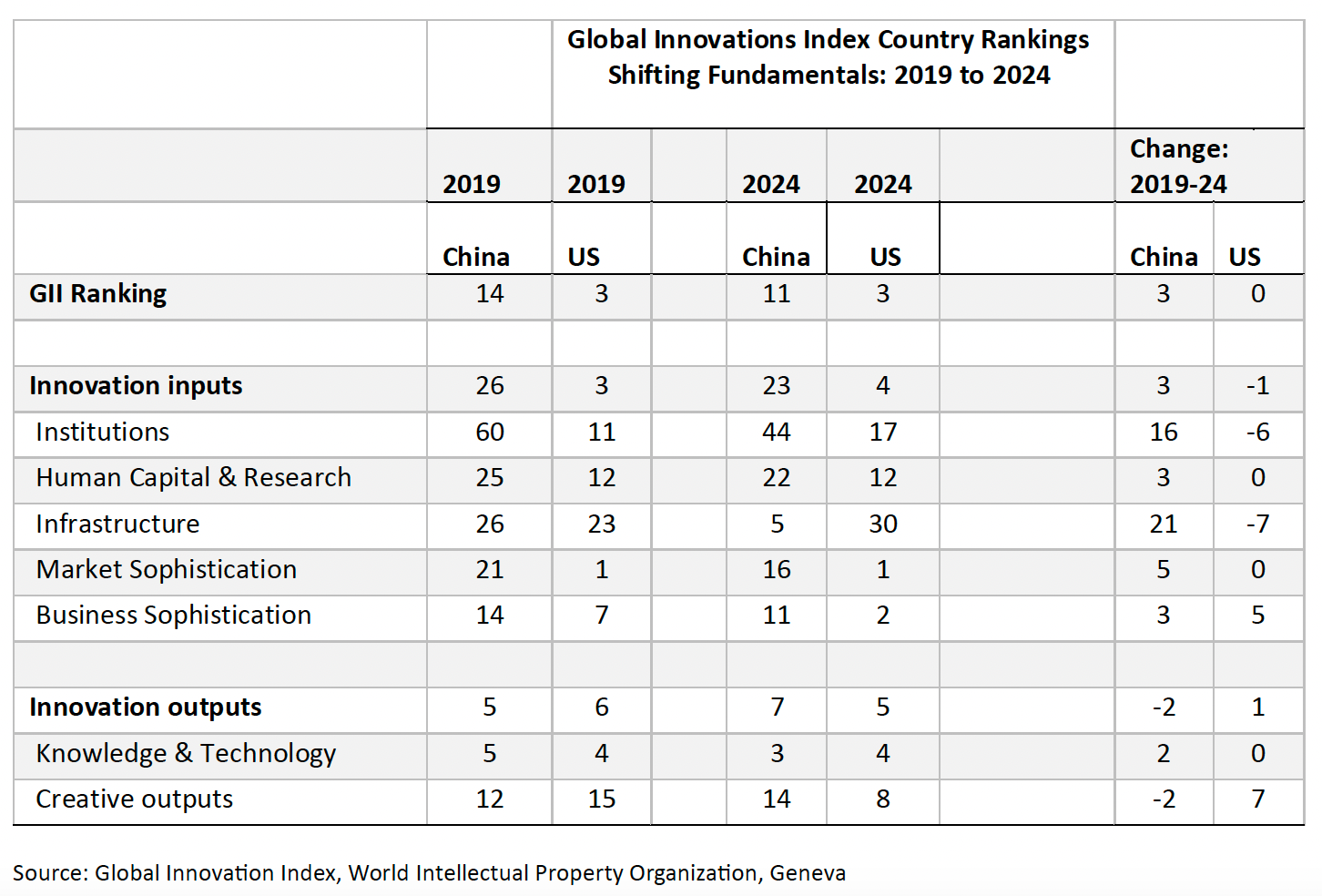

The table below provides a more detailed assessment of the shifting fundamentals of the US-China GII comparison over the most recent five-year period, 2019 to 2024. The two columns on the far-right measure five-year shifts in country rankings of the two countries, broken down into their respective functional categories on the input and the output sides of the GII-based innovations framework.

Of particular significance are two key sources of China’s recent improvement in innovations inputs — institutions and infrastructure. At the same time, the sharpest deterioration for the United States came in the same two categories. Institutions, as seen through GII metrics, have more to do with the government’s regulatory effectiveness in promoting a stable business operating climate. China’s improvement came in two subcategories of the business environment — policy stability for doing business and entrepreneurship policies and culture; this latter finding is not without controversy considering China’s regulatory crackdown on Internet platform companies beginning in late 2020. By contrast, for the US, deterioration was evident in components measuring support from the regulatory and political climate.

In terms of innovations infrastructure, GII metrics underscore China’s significant improvement in information and telecommunications technologies (ICT) over the latest five years, both from the standpoints of access and usage. For the US, slippage in the infrastructure rankings was concentrated more in what the GII dubs “ecological sustainability” — especially alternative energy and environmental pollutants. Also of note on the input side, was China’s number one ranking on PISA scores (Programme for International Student Assessment) for 15-year-old secondary students in reading, math and sciences, up sharply from the number eight position in 2019 and well above the US position of 17th in 2024. [Note: This GII-based ranking is slightly at odds the 2022 OECD assessment, which put Singapore’s PISA results fractionally ahead of China.]

For the two major gauges on the output side of the GII innovations framework, China’s most notable accomplishment over the past five years is that it closed the gap with the US in terms of knowledge and technology. This reflects especially impressive performance in “knowledge diffusion” — driven by gains in intellectual property receipts and so-called high-tech exports — and sustained top-five rankings in “knowledge impact” as reflected in the value of start-ups and software spending as a share of GDP. In terms of creative outputs, China sustained its number one ranking for intangible assets (i.e., trademarks and industrial design), whereas the US scored considerably higher in “online creativity” and in a catch-all category of creative goods and services.

So, what are we to take from these comparative metrics on the US-China innovations race as seen through the lens of GII results? I would offer three tentative conclusions:

First, America’s innovations containment strategy, especially the “small yard, high fence” sanctions-based approach of the Biden Administration which appears to be very much intact in Trump 2.0, is way off the mark when it comes to China. In keeping with China’s historic legacy as the world’s leading innovator, GII metrics confirm broad-based legitimacy to China’s rapid ascendancy as a rising leader in the global innovation sweepstakes over the past decade.

Second, the GII results of the past five years underscore China’s focus on the building blocks of innovation — notably ICT infrastructure, secondary school educational attainment, and a results-oriented research culture that is now leading the way in patents and copyrights. It is hardly a coincidence that these results are tightly aligned with a major industrial policy initiative, “Made in China 2025,” that was launched in 2015. Unsurprisingly, China has been very focused on laying the groundwork for innovation, underscoring its potential for sustained AI prowess.

Third, while the US appears to be holding its own from the standpoint of its overall GII position — remaining in third place in 2024 behind Switzerland and Sweden — there are some worrisome signs starting to appear on the inputs side of the innovation equation. That is especially the case with ICT infrastructure and the government’s institutional commitment to an innovation-enhancing business start-up culture.

GII metrics were originally developed to embrace a broader concept of innovation than traditional measures, which had long focused on the link between innovation and research and development (R&D) expenditures. With its coverage of now some 133 countries, based on 78 individual metrics, the GII offers a detailed assessment of apples-to-apples innovation metrics. While this type of framework allows us to examine a comprehensive overview of the ebb and flow of innovation across borders, it misses some important country-specific developments that could well be decisive in shaping the global innovation race.

That is especially the case when it comes to the innovations battle between the US and China. Particularly worrisome is diminished US emphasis on Federal government support for the key basic research component of R&D spending. Equally disconcerting is the Trump Administration’s recent DEI-focused assault on scientific research and higher education, as well as the anti-collaborative mindset of an increasingly worrisome Sinophobia that has now gripped America. At the same time, China’s unique strain of state-directed innovation, tied to the mounting excesses of a seemingly chronic overhang of excess capacity, exacerbates the stakes of the innovations battle between the two superpowers.

If you believe the latest surveys and a slew of new books, nothing short of the future of humanity is at stake in the great battle for AI supremacy. Far be it for me to make light of this debate. But I think we must be careful and objective in assessing the arguments. The indicator approach of the GII provides a useful framework to assess the multiplicity of common forces influencing the global dispersion of innovation. Its weakness lies in an arbitrary weighting scheme that brings together many pieces of the innovation puzzle in assembling an overall GII metric. The GII is not the final word on innovation. I will discuss other considerations in an upcoming dispatch. In the meantime, take a deep breath before reaching a panicked conclusion on the Sino-American AI race.