AI Déjà Vu

The AI spending boom is a bubble — reminscent of that which sparked a major wave of services restructuring in the 1990s.

There is no doubt that AI is revolutionary. There is good reason, however, to doubt, the over-the-top responses of US businesses and financial markets to this revolution. Borrowing a page from boom-bust cycles of the past, the possibility of an AI spending bubble deserves serious consideration.

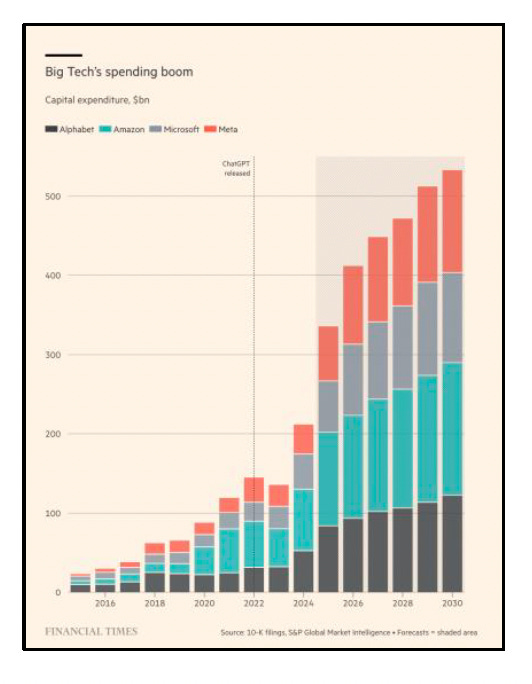

The chart below, courtesy of the FT, highlights the explosive surge of spending planned by America’s four largest AI companies — Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft, and Meta. Their combined capital expenditure budgets are expected to increase nearly three-fold from 2024 to 2030. This surge reflects expectations of massive expansion of data processing centers to match an equally large explosion in the anticipated use of large language machine-learning AI models. This spending, estimated at a little over $200 billion in 2024, or about 5% of total capex, is expected to surge to nearly $550 billion in 2030.

This AI-related spending binge is likely to be the strongest source of growth in an otherwise sluggish US growth climate. Needless to say, if the economy slips below consensus growth estimates (a CBO baseline trajectory of only 1.8% real GDP growth over the 2025-30 period), capital spending budgets will likely be revised downward — even those supporting the new AI miracle.

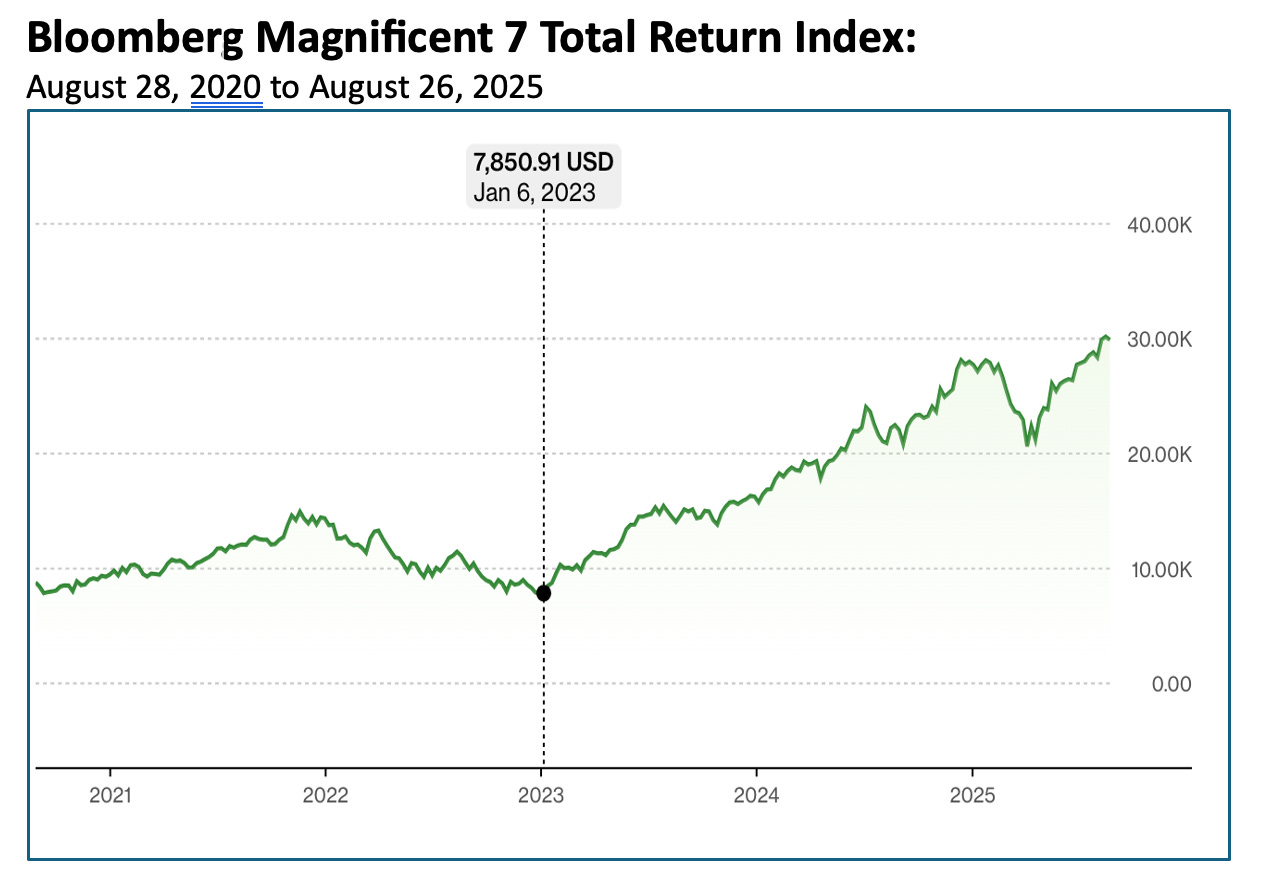

With that caveat aside, the scale of this extraordinary increase has not been lost on the US equity market. The so-called Magnificent 7, a Bloomberg composite equity index which reflects share prices of a broader group of America’s leading AI companies that also includes, Nvidia, Apple, and Tesla, currently stands nearly four times the level prevailing in early 2023 (chart below). It has more than recouped sharp losses earlier this year that occurred in the immediate aftermath of the emergence of the “DeepSeek threat” — a Chinese AI start-up capable of delivering machine learning results comparable to OpenAI’s ChatGPT, but at significantly lower costs. As is often the case in a bubble, investors, steeped in denial, ended up dismissing this threat — possibly with great regret. I noted in an earlier post that Mag 7 concentration risk in the broader S&P 500 has now moved to extremes that are more than six times those seen by Internet stocks at the height of the dotcom bubble in March 2000.

There is a striking sense of déjà vu to this development that has its roots in the capital spending binge of the 1990s. Business fixed investment grew at a 9.5% average annual rate from 1992 to 2000, expanding from 11.4% of GDP to 14.6% over this 8-year interval. At work was the first wave of a powerful boom in information technology spending.

My research at the time, which eventually made it into the Harvard Business Review, revealed that the bulk of this spending was driven by relatively low-value added back-office automation. It was concentrated in transactions-intensive services companies — banks, insurance companies, telecommunications, retailers, and airlines. I argued that this was a bubble, as individual finance companies, for example, were putting enough processing capacity in place to clear trades and transactions for the entire industry. Not only was this an ominous overhang of excess data processing capacity but there was a worrisome transformation of corporate cost structures: heretofore variable cost companies, whose main assets used to be people that went down the elevator every day, were unwittingly turning themselves into increasingly fixed-cost producers. When the workers left the office, the IT infrastructure remained in place long after the end of the workday.

A massive services sector restructuring was at hand, I concluded. And that is pretty much what happened. The number of US banks plunged from nearly 11,500 in 1992 to 8,3000 in 2000. There were comparable directional shifts in the population of other transactions-intensive services providers. The inhouse excesses of data processing and credit functions were either spun off (i.e., American Airlines’ SABRE or Morgan Stanley’s Discover) or outsourced to third-party providers (such as ADP); these spin-offs and start-ups were more flexible variable-cost providers, whose main business line was data processing.

That story has eerie parallels with today’s AI-related capital spending binge. Each of the four companies featured above has created, at considerable expense, proprietary AI search engines, based on the inhouse development of unique LLM algorithms. But there is nothing unique about the raw processing capacity needed to deliver instantaneous search results. Moreover, the DeepSeek Chinese alternative raises serious questions about AI processing requirements per unit of LLM output, to say nothing of the energy intensity of the massive, expected build out of AI-driven search processing capacity.

Amazon, with its AWS (Amazon Web Services) subsidiary, appears to be the closest to figuring this out. Microsoft Azure (now Entra) and Google Cloud are also moving in that same direction. But the subsidiary approach ultimately is not the answer for the larger parent that is now taking on the trappings of a fixed-cost AI-driven processing function. Earnings and share-price valuation of the parent will undoubtedly reflect this transformation of the cost structure. Moreover, the wide-ranging functionality of these subsidiaries, which goes well beyond machine-learning support, is likely to dilute the “pure AI” play in the equity market.

Like services sector restructuring of the 1990s, there are more effective options — spin-offs, stand-alone start-ups, or joint ventures — to separate the costly excesses of low-return LLM processing from the higher-value added functionality of new proprietary AI algorithms. Early signs of such a trend are already evident in the form of so-called hyper-scale data center developers, such as Digital Reality, QTS, CyrusOne, Skybox, VAST Data, and AirTrunk (Australia) — each of which aims to provide dedicated LLM processing for multiple AI vendors.

Offloading fixed cost, low value processing in favor of a more variable cost focus on core AI strategies is likely to continue. The coming data center spending binge is an early warning of the coming restructuring of the largest, “Mag-7-like”, AI companies. At the same time, this could well have important implications for the likely unwinding of AI-related concentration risk in equity markets.

Again, it’s not the AI revolution that I am drawing into question — although some appear to be doing that as well. My concerns have more to do with a “ride-the-wave” mentality to the AI boom. The confluence of short-sighted business decision making and classic investor denial has long been the epitaph of bubbles in the past.

The number of US banks plunged from nearly 11,500 in 1992 to 8,3000 in 2000.

8300?or 3000?