The Delusional Dollar (corrected)

While the US dollar didn't fall as I thought four years ago, there is a far more compellinfg case today for a sharp decline in the Greenback.

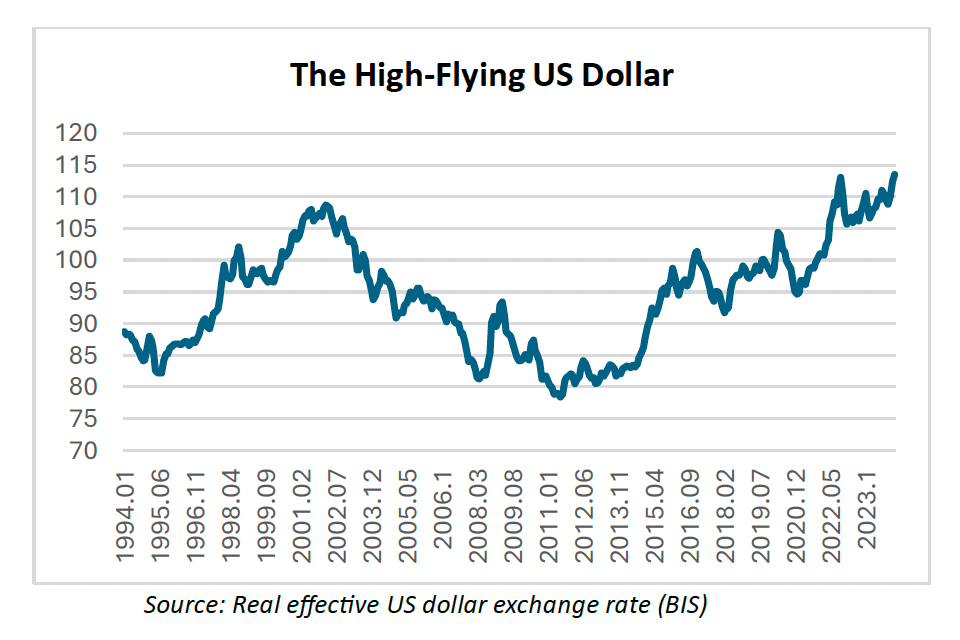

As something of a congenital contrarian, I have always been suspicious of one-way trades in financial markets. Last week, I took a stab at the AI bet. In what follows, I turn my focus to the US dollar, currently at an all-time high. The consensus mindset is that nothing can stop the never-ending ascent of the Greenback. I think there are compelling reasons to challenge this view.

Yes, I tried that before with an embarrassing wrong-way call for a dollar crash that was originally published in mid-2020. Unfortunately, at least for my forecasting record, the US currency went precisely the other way; the broad dollar index soared by 20% from January 2021 to December 2024 (as measured in real effective terms by the BIS), one of the strongest four-year upsurges on record. The case I made rested largely on a potentially lethal interplay between subpar domestic saving and an historically wide current account deficit. Something had to give, I argued. A weaker dollar would be the escape valve from those seemingly unsustainable macro tensions. Alas, as I admitted in my mea culpa in mid-2022, the main source of my error was a surprising about-face of the Fed, which quickly went from a passive response to post-Covid inflation to an aggressive monetary tightening in 2022-23. I should have known better. The haunting words of Alan Greenspan still ring in my ears — that forecasts of directional shifts in the dollar are no better than tossing a coin.

When you make a terrible call, like I did with the dollar crash, it is very human to shy away from saying another word about something you got so wrong. I confess that there is a part of me that is still tender from the wounds of blowing the dollar call a few years ago. Undaunted, probably to a fault, I have long adhered to my strongest convictions. In that spirit, I once again raise several critical concerns about prospects for the US dollar:

First, and an echo from my initial call, are the fundamentals of a gaping current account deficit and anemic domestic saving. Both metrics are in considerably worse shape than they were four years ago (chart below). The current account deficit widened out to -4.2% of GDP in the third quarter of 2024, well in excess of the -1.85% gap in early 2020 when I initially made my bearish call on the dollar. As I have stressed ad nauseum, the current account imbalance doesn't arise out of thin air — it is tightly linked to the demand for surplus foreign saving that stems from a shortfall of domestic saving. On that count, the net domestic saving rate stood at just 0.4% of national income in the third quarter of 2024 versus 3.1% in early 2020. Moreover, with prospects for large budget deficits in Trump 2.0, it is a stretch to imagine any meaningful improvement in domestic saving that would be required for a narrowing of the current account deficit. Consequently, the likely persistence and increased intensity of these macro tensions should put even more downward pressure on the dollar than was the case four years ago.

Second, is an assessment of Fed policy risks — the wildcard that derailed me four years ago. As the US central bank belatedly recognized that the post-Covid inflationary scare was far more than just a transitory development, it orchestrated an aggressive shift in relative interest rates that favored returns on dollar-denominated assets. With the federal funds rate now much closer to “neutral” than it was four years ago, the risks of another aggressive monetary tightening have all but been taken off the table. As inflation came down sharply from its 9% spike in mid-2022, the Fed unwound a little less than 20% of its cumulative tightening of 530 basis points that occurred during the 2022-23 period. Even if above-target inflation remains stubbornly persistent — a point that was not lost on the markets this week with a surprisingly sharp 0.5% increase in the January CPI — the odds of another aggressive dollar-friendly Fed tightening are considerably lower than they were in early 2020.

Third, is the possibility of cross-market contagion. If I am correct in the argument I made last week that the AI-led US equity bubble bursts, I suspect there will be collateral damage in other over-valued US asset markets. The high-flying US dollar is unlikely to be spared. This seemingly flies in the face of the dollar’s Teflon-like safe-haven stature — that global investors invariably seek refuge in the world’s safest asset, the global reserve currency. Is this time different? Dangerous words, I know. But when major asset bubbles burst, finding shelter in an over-valued safe haven becomes especially problematic.

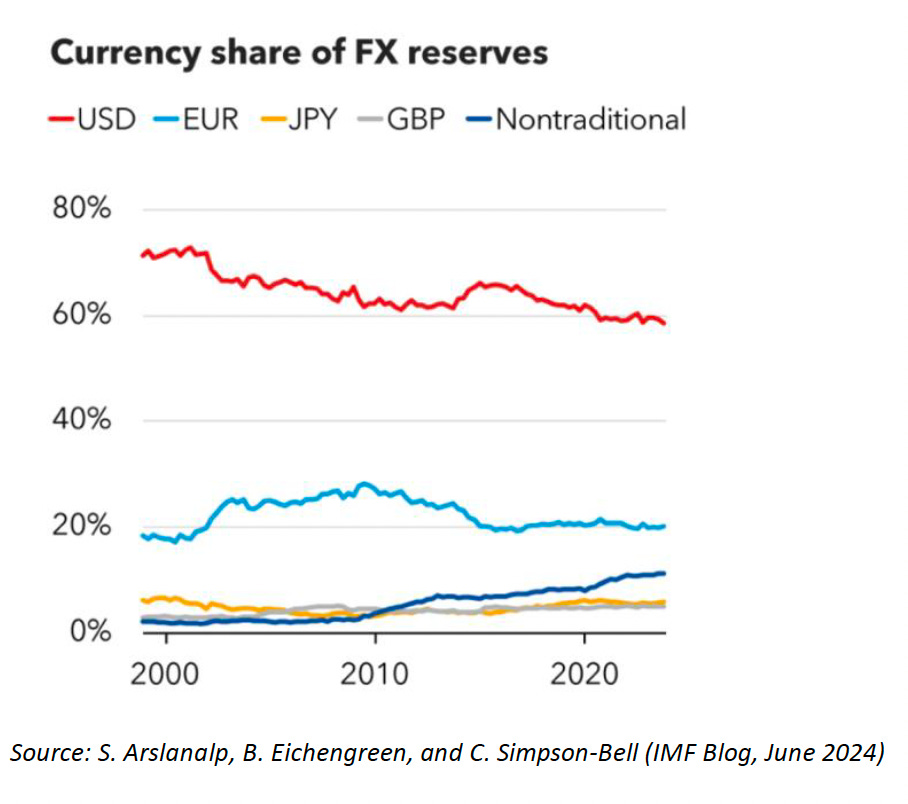

Fourth, and related to the third point, is the longstanding special role that the dollar enjoys as the world’s major reserve currency. Over the years, there have been repeated calls for the dollar’s dethroning as the anchor to the international financial system. While there has, in fact, been a steady decline in the US dollar’s share of official foreign exchange reserves, there is no other major currency that comes close (see chart below). The consensus view is that the dollar’s reserve status will only be challenged, if ever, at some point in the very distant future.

While that still seems like a reasonable bet, there are several considerations that may point to an earlier day of reckoning: For starters, the dollar’s share of global FX reserves has been artificially inflated by both dollar appreciation and by favorable US interest rate spreads; adjusted for these distortions, the dollar’s share is closer to 55% than the 60% share indicated in official IMF statistics (see chart below). In addition, there are signs of a post-globalization clamoring for regional reserve currency blocs, led by the so-called Global South. And there are the lessons of history; as Barry Eichengreen argued in his seminal book, Exorbitant Privilege, sterling’s once dominant reserve status ended up being more fleeting than widely thought.

Fifth, is the dollar’s great allure wrapped around its fuzziest underpinning — American exceptionalism. We always seem to argue about the staying power of this amorphous concept. To be sure, this is a multifaceted construct — reflecting the combination of military and economic/ financial strength, along with the underpinnings of morality and character that are presumably befitting of global leadership. All of which raises the obvious and important question: Are those attributes now more, or less, at risk in the MAGA value proposition of Trump 2.0? This is obviously a hugely contentious issue in today’s polarized American climate. But, at a minimum, I would offer the following observation: The territorial ambitions of a modern-day strain of a McKinley’s Manifest Destiny — Greenland, the Panama Canal, and even Canada — frame American Exceptionalism in a very different light today than was the case when I first turned bearish on the dollar in 2020. To put it in Reaganesque terms, is the over-valued dollar pricing America to be an even brighter “shining city upon the hill” than it was a generation ago?

Finally, and what some might consider today’s most important consideration, the seemingly all-important tariff angle. Currency markets are priced for what I would call a knee-jerk conclusion on tariffs — that by constraining US demand for imports, tariffs lower demand for foreign currency, thereby providing a relative boost to the demand for US dollars. This is a superficial interpretation, at best. Significantly, it ignores likely tit-for-tat retaliation of other countries, which would reduce their demand for dollars. While the US imports far more than it exports, it still sold nearly $3.2 trillion of goods and services overseas in 2024, underscoring the considerable scope for dollar-negative retaliation. And then there is the whole body of thought criticizing US tariffs as a tax on American consumers, a serious complication for Fed policy and interest rates, and a potential trigger to a global trade war. This latter possibility is all the more worrisome in light of President Trump’s recent proposal for “reciprocal tariffs,” actions that could spark further rounds of retaliation from US trading partners that could well culminate in a race to the bottom for an interconnected, still globalized world economy. Amid such a cascading chain of events, it seems to me to be nothing short of a self-serving stretch to depict US tariffs as a positive for the dollar.

So, there you have it — yet another case for a sharp decline in the US dollar. Notwithstanding the obvious caveat of my terrible recent track-record as a currency forecaster, I am willing to go out on a limb once again in looking for the broad dollar index to retrace most, if not all, of its sharp 20% gains over the past four years. I will adhere to the Golden Rule of forecasting — offering directional guidance but no date. When the dollar goes, and under what circumstances, is guesswork beyond my paygrade.

In the end, it is important to remember that the dollar is, first and foremost, a relative price — an assessment of all the factors shaping the intrinsic value of US assets compared to those inherent in assets elsewhere in the world. This goes back to the point I made last week. Safe haven, or not, there can be no denying the delusional strength of vastly overvalued assets. That’s the real risk to both AI-led equities and the US dollar.

[NOTE: For some inexplicable reason, the Substack editor has removed all linked references from this piece. For those in need of a fully-linked version, please email me directly. Apologies.]

Thanks for all your feedback. One other point worth noting here: I agree that TINA (there is no alternative) seems to be a very seductive counter to my case. But that doesn’t rule out cyclical corrections of an overvalued dollar, of which there have been three key episodes post Bretton Woods — 1970-78, 1985-88, and 2002-11. Average declines in the dollar’s real effective exchange rate in those three period was -31%. And the dollar’s share of FX reserves during those periods was above 70% — today that share is well below 60%. Dollar dominance — albeit eroding — doesn’t negate the gravity of a fall from unsustainable heights.

Spot on, and I both admire and applaud your willingness (eagerness?) to take another bite at the apple. Right or wrong, your thought process is sound and deserves to be taken seriously. Thank you.