Spin Art

The tariff shock — from soft to hard data.

The art of the deal apparently can mean almost anything. Trump bets the limit on a pair of deuces – 145% tariffs on China — then probably folds and calls it a deal. Crypto, Greenland, and Canada — same story, all spin and no substance. But the tariff gambit is different — it promises lasting damage to America and its once cherished reputation as that shining city on a hill. The House loses.

Meanwhile the global economy is now heading into the danger zone. While the data flow is always choppy near business cycle turning points, early warning signs from soft data are already flashing amber. That includes surveys of consumer and business sentiment, which are available on close to a real-time basis. It also includes purchasing managers’ sentiment, which capture monthly shifts in perceptions of business production managers. To be sure, while soft data are useful as leading indicators, they offer nothing in the way of hard data points that eventually get incorporated into the official metrics of national income and product accounts. That comes later — with a lag.

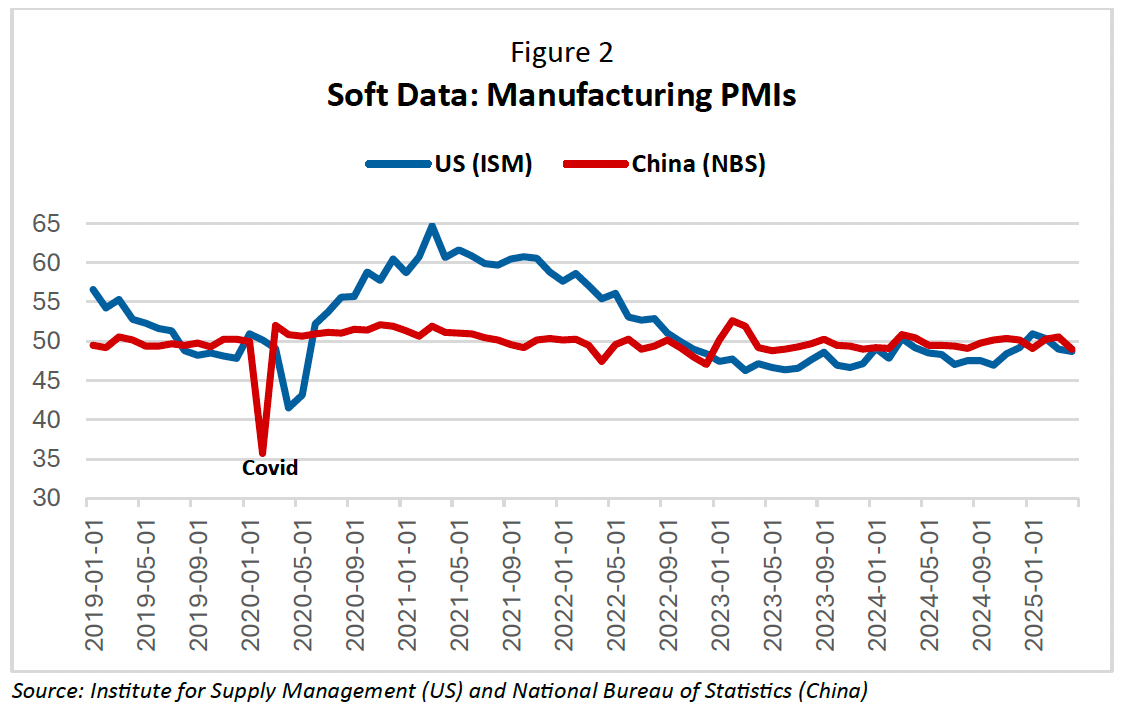

Recent trends in the soft data in the United States are, unsurprisingly, soft. Since Trump’s April 2 Liberation Day pronouncements, consumer sentiment has plunged while the purchasing managers’ activity index (PMI) has moved below the all-important “50 threshold” for the second month in a row, typically signaling a contraction of manufacturing activity. Moreover, major components of the manufacturing PMI — orders, production, employment, inventories, and delivery times — all moved to the downside while there was a notable increase in pricing pressures.

One month hardly makes a trend, but the broad contours of US soft data on consumer and purchasing managers’ sentiment are flashing early signs of stagflation. Time will tell if this trend persists and is confirmed by hard data. Shipping data from the Port of Los Angeles, one of the best windows on US exposure to Chinese trade flows, points to a 35% to 45% downdraft from year-earlier rates that is only a matter of days from showing up in the hard numbers.

For China, the soft data point to a similar set of reactions by consumers and businesses, alike. China’s manufacturing PMI also dipped below the “50 threshold” in April, driven by a precipitous decline in new orders. Chinese consumer confidence data are less timely but have been beaten down in recent years by the twin forces of property market pressures and high levels of youth unemployment. With punitive tariffs putting severe pressure on Chinese export industries — after all, it is their shipping traffic which has been reduced — that sentiment will only worsen. That’s hardly a big secret to Chinese policymakers. It was validated by a recent pre-emptive policy easing by the People’s Bank of China aimed at limiting the mounting downside to the Chinese economy.

A key issue for economists and policymakers is the connection between soft and hard data — in effect, whether there has been enough damage to sentiment to trigger sharp responses in the real economic decisions of production, employment, and capital spending. If that turns out to be the case, then knock-on effects to income generation and personal consumption become inevitable, sealing the fate for a cumulative decline in the business cycle. Unsurprisingly, there were no meaningful signs of such a reaction in the just-released April employment report in the US. Labor markets are typically a lagging indicator of broader turns in the US business cycle. Financial markets may have breathed a premature sigh of relief.

Identifying pain thresholds in soft data can be tricky. Figure 1 below compares the soft data on consumer sentiment for the US and China from 2019 to early 2025, allowing for a comparison between the Covid shock of early 2020 and the current tariff-related dislocations. The Chinese data only run through January 2025, failing to capture the current intensification of US-China trade frictions. Two points jump off this chart: First, the sharp recent drop in US consumer confidence is already comparable to that which occurred during Covid; second, relative to pre-Covid readings, the tariff shock is currently hitting US and Chinese consumers at already depressed levels of confidence, hinting at a thinner cushion of resilience that may have lasting consequences for prospective consumer support in both economies.

Figure 2 highlights the US-China comparison for manufacturing activity as seen through the lens of Purchasing Mangers’ Indexes; in this case, data for both PMIs run through April 2025. Three points worth noting: First, dramatic Covid-related lockdown effects occurred in early 2020 in both countries; second, post-lockdown snapbacks were far more robust in the US than in China — consistent with China’s lingering “zero-Covid” hangover that lasted through 2022; and third, despite having just pierced the “50 threshold,” production shortfalls from the tariff war have been relatively limited so far in both manufacturing sectors.

It’s obviously early days in picking up measurable impacts of the tariff shock in either the Chinese or US economies. For now, such an outcome is only a forecast of a highly uncertain future. And it’s a forecast that will also have to contend with one of the most powerful forces that always shape economies and markets — momentum. It is often said that supertankers don’t turn on a dime, a particularly apt metaphor today. That is especially the case for the world’s two major growth engines — the US and Chinese economies. Rare is the sudden-stop crisis that brings economic activity to an abrupt halt The lockdown of Covid-19 was the exception, not the rule. The difference between these two shocks couldn't be starker: The pandemic led to an immediate, all-encompassing lockdown of economic activity that was quickly followed by the rebound of a reopening; barring a prompt reversal of tariffs, there is no promise of such a self-correcting endgame in a trade war.

The good news is that both Beijing and Washington finally appear to have recognized the gravity of these circumstances. De-escalation is the stated purpose of this weekend’s meeting between senior economic leaders of both nations — US Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent and Chinese Vice Premier, He Lifeng. What that means is anyone’s guess. I suspect there will be some form of a joint rollback from unsustainable triple-digit tariffs currently in place. I am not dissuaded by Trump’s denial of such a gesture. It’s all part of the art of the bluff. The art of the spin — on full display in today’s Oval Office celebration of a “framework deal” with America’s fifth largest surplus trading partner (the UK) — underscores how far Donald Trump will go to boast of a bilateral agreement that does nothing to reduce a record US multilateral trade deficit.

Irrespective of the outcome in Switzerland, I think there is a high likelihood that tariff rates will remain onerous on both sides of the US-China trade equation. Even under the new agreement, the UK will still have to face a 10% tariff floor — and China, a good deal higher. That will be insufficient to prompt a major resumption in cross-border trade between the world’s two superpowers, making it too late to prevent sharply reduced container-ship arrivals in the United States over the next several weeks, if not sooner. That will keep the soft data soft, implying that it is only a matter of time before the hard data follow suit. Don’t be misled by the all too predictable art of the spin.

Why? Always an interesting question. In my unified theory of our dilettante leader, all roads lead to the big beautiful extension of the tax cuts.

Blow away the smoke and break the mirrors and what we are left with is a singular focus on extending the tax cats. Period. That’s it.

The tax cut extension has zero chance in the Senate (and maybe the house) and so the yellow brick road follows the rules of reconciliation which require tax revenue neutrality. Thus cut costs and raise revenues.

Elon does the Doge cost reductions and The Donald raises revenue with the tariffs (aka Import Taxes).

When he lowered tariff rates he could not get to revenue neutrality so he raised Chinese import taxes to offset.

Navarro / Musk et al are simply looking for a combination of $600 billion a year to argue revenue neutrality to allow for a simple majority vote on the tax extension.

Thus, consumers are funding the wealthy’s tax cuts. Period. Do democrats care? No! They have wealthy donors also. So our political class rolls over, will let it pass and then take credit (MAGA) or cast aspersion (Dems).

In the meantime the clock is ticking on our debt time bomb. No one is coming to help us and old man Trump will be gone when it explodes.

Ask yourself, at what debt level does it all blow up? $50, $75, $100 trillion?

Trump hit the pause button on Import Taxes because the 3-year US Treasury auction was going to fail. Japan and China are reducing their holdings. How high will rates go, how steep will the yield curve get, when will the Fed be in control like SCOTUS?

Why buy equities when 4+% is available in cash?

Good luck folks.