Imagining Engagement, Part I: Defining the Goal

Look before leaping. Prior to making the case for US-China engagement, it is critical to understand what that might entail.

There is literally no constituency in the United States currently in favor of Sino-American engagement. That is most assuredly the case in the US Congress, where anti-China sentiment enjoys unanimous bipartisan support. It is also the case in established US foreign policy circles; a 2018 Foreign Affairs article by Kurt Campbell and Ely Ratner, “The China Reckoning,” has led the recent charge.

Even in academic circles, a large stable of China scholars has surrendered any semblance of hope in a constructive future for what had long been billed as the world’s most important relationship. David Shambaugh, with his extraordinary pedigree of some 29 books on China, is a case in point. His latest book, Breaking the Engagement (2025), concludes with a resoundingly dire statement that “… the US strategy of engagement is dead. D-E-A-D.” By repeating and offering a Trumpian-like capitalization of those four letters, Shambaugh essentially rules out any possibility that the two superpowers might repair a deeply damaged relationship. He is hardly alone.

I reject this four-letter assessment. I take that view not as a contrarian, but as an advocate of the mutual benefits both nations are in danger of squandering. But that is not the point of what follows. First, I want to raise the more basic question of what US-China engagement might look like?

I think we have to be especially imaginative in answering this question. The only thing I am certain of is what worked in the past is not a recipe for the future. Starting with US President Richard Nixon and Chinese leader Mao Zedong in the early 1970s, engagement between the two nations has relied heavily on leader-to-leader chemistry. Personalization, especially in the form of grand summits between the nations’ two leaders, has had an enduring influence on subsequent efforts at US-China engagement.

There is hope for a similar outcome in the not-so-distant future, especially since Presidents Trump and Xi have tentatively agreed to a new round of meetings later this year. Alas, don’t hold your breath for a miraculous breakthrough. I remember all too well their two earlier summits in 2017, briming over with bromantic toasts and great promises, only to be quickly followed by the first rounds of tariffs in 2018-19.

An enduring engagement between the United States and China needs far more than leader-to-leader stagecraft. What worked in the 1970s, when there was literally no relationship between the two nations, is unlikely to do so today, when the connection between the two superpowers is deeper and far more complex. Conflict has exposed the fault lines of personal chemistry, reflecting the very human flaws of ego-driven leaders, overly sensitive to domestic political pressures, and in the case of Donald Trump, a leader who is susceptible to hyper-volatile shifts in positions that have unfortunately been countered by China’s equally volatile penchant for tit-for-tat retaliation.

If there is ever to be a constructive future for the Sino-American relationship, it will need to go well beyond the fragile personalization of leadership diplomacy. A durable engagement that can withstand the stresses and strains of inevitable frictions and conflicts must check five key boxes:

Goals. This is as much a political as an economic statement. The United States and China have both framed their values and goals in terms of “national dreams” — the Chinese Dream and the American Dream. These two dreams focus broadly on prosperity, equality, and opportunity. But they also reflect strong nationalistic determination aimed at overcoming difficult periods in the past; the Chinese Dream focuses on an outward-facing rejuvenation of its role as a world power after a “century of humiliation” while the American Dream was first articulated in the depths of the Great Depression. Both nations draw aspirational strength from the desire to overcome painful periods in their history. Goal setting need not be the same for both nations, but each should have a clear understanding of where the other is coming from.

Common ground. The building blocks of engagement rest on an honest inventory of each nation’s existing state of affairs. From an economics standpoint, that turns the focus on structural imbalances — namely, internal vs. external demand, consumption vs. investment, saving vs current account imbalances, demography vs AI-related job displacement, as well as inequality of income, wealth, and opportunity. This inventory should serve as a starting point to develop a joint recognition of the overlap of strengths and weaknesses that will condition collective relationship expectations for the future. In the same sense, there will undoubtedly be areas of disagreement that do not lend themselves to engagement; that’s true on economic grounds (i.e., so-called “negative lists” in foreign investment policy) and on political grounds (i.e., ideological clashes between different systems). It is important to respect and own these differences, as well, in setting realistic expectations for collaborative engagement.

Policy. The combination of goals and common ground should be seen as the broad outline of a mutual policy-setting agenda. From an economic perspective, this will undoubtedly sharpen the focus on matters of trade policy, investment policy, innovation policy (including Artificial Intelligence) as well as on the critical global issues such as climate, world health, cybersecurity, and human rights. Equally important here will be a joint assessment of existing agreements and institutions in light of predetermined goals and common ground. Discussions over trade agreements, potential bilateral investment treaties, AI standards, global health and climate protocols, should be framed with the key considerations of goal setting and common ground in mind.

Exchange. Decoupling is a huge and growing risk for the US-China relationship. Decoupling can occur at many levels — through bilateral trade flows, financial capital, and the exchange of digitized information. But decoupling can also be manifested through breakdowns in scientific and educational exchanges, as well as by a cessation of dialogues between officials and experts in the two nations and their governments. Exchanges are the glue of engagement, providing catalytic energy to expanded interactions over time; this latter point is especially true of student exchanges, the seed corn of future expertise that each nation requires to develop a better understanding of the needs of the other. Reduced exchanges have a corrosive impact on relationship integrity that renders engagement all but impossible. Recapturing and building upon an earlier spirit of exchange is essential for re-engagement.

Verification. Talk is cheap and documents are both legally contentious and, ultimately, disposable. As such, agreements won't work without a mutual consensus on a robust verification framework — including oversight, compliance, dispute resolution, and pre-determined enforcement penalties. National security considerations, an increasingly contentious source of angst and conflict for both the United States and China, must be integrated into such a verification framework. This will not only entail a transparent assessment of “dual use” technologies but also unmask a securitization of supply-chain vulnerabilities. Engagement need not be seen as a threat to national security but instead as the means to reinforce alliances with a more secure and robust bilateral connectivity. In the end, verification is the essence of trust — the five-letter word that must replace the four-letter mindset currently poisoning the US-China relationship.

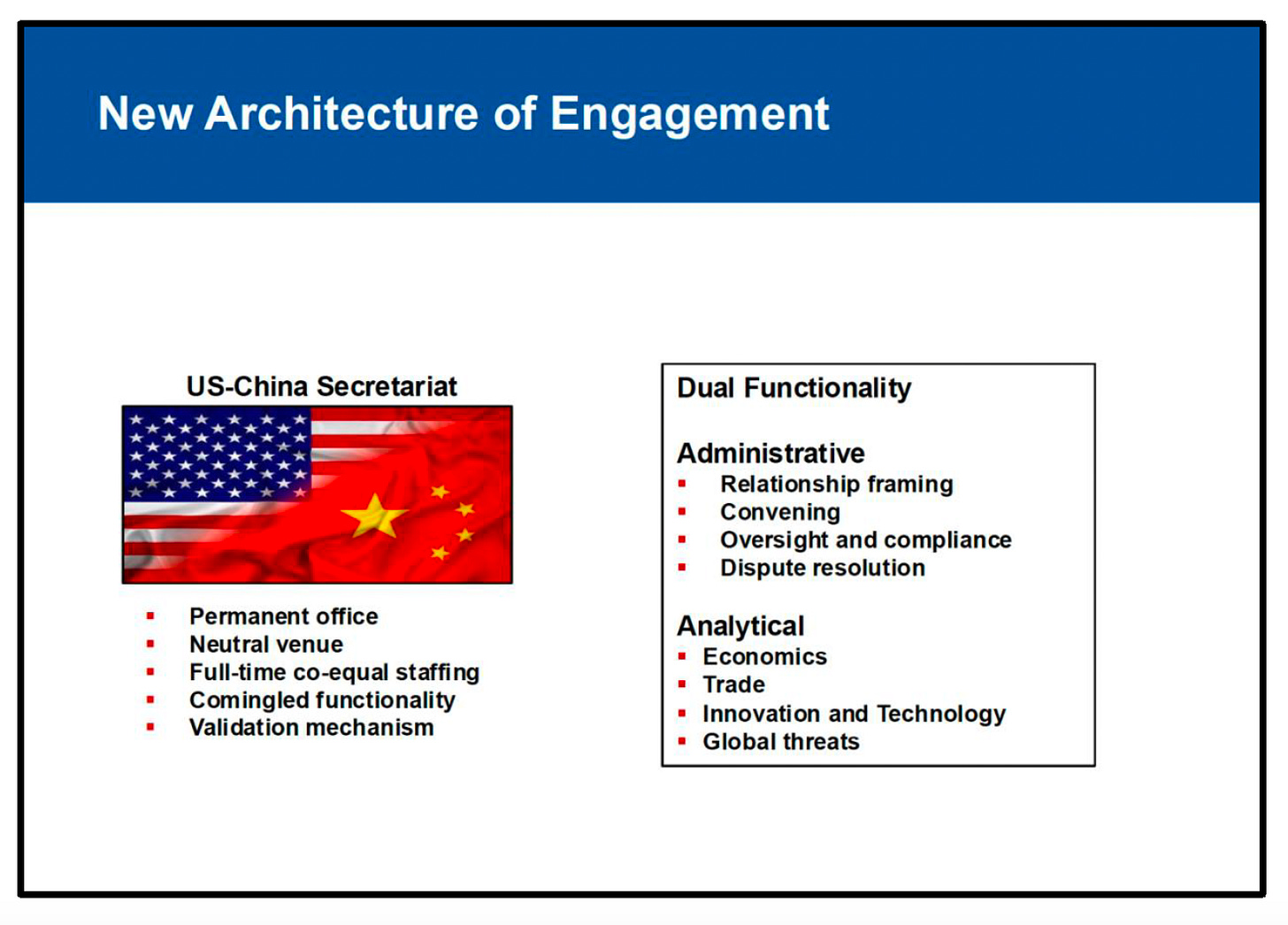

A few additional points at this stage: First, in keeping with my introductory comments, I am framing engagement as more of a depersonalized effort rather than emphasizing the personal approach embedded in leader-to-leader legacy efforts. This is not meant to diminish the potential of diplomacy as a means to engagement, but to stress that diplomatic efforts, while necessary, are not sufficient to insure a durable engagement. Stand-alone diplomacy will inevitably fail if it is not accompanied by an institutionalized platform of engagement. I have written extensively about a US-China Secretariat that is aimed at making the institutionalization of engagement operational (see below). More on that later.

Second, and a pet gripe of mine, the experts have spent far too much time on nomenclature — coming up with catchy new phrases that purportedly capture a major shift, or a new focus, in the US-China relationship. The names and concepts span the gamut: strategic competition, assertive competition, competitive coexistence, strategic ambiguity (Taiwan); a new model of major country relationships (Xi Jinping), strategic partnership; strategic competition, co-opetition, responsible stakeholder, and so on. I am not looking for a clever new a-ha concept that rings the bell in both Washington and Beijing. Engagement between superpowers is a very complex, multi-dimensional concept that defies the catchphrase.

Finally, I want to reiterate the point of this dispatch: Prior to making the case for engagement, it is critical to understand what the concept entails. I concede that the five ingredients, or characteristics, of US-China engagement stressed above barely scratch the surface of this weighty topic. They are intended, instead, as an outline for a first draft on what US-China re-engagement might look like. I am not asking for buy-in — at least not now. But I want to be transparent on what the concept of engagement might look like. It is always important to look before leaping.

As I argued in my most recent book, engagement is as much a political challenge as an economic imperative. Conflict, the antithesis of re-engagement, cannot be resolved until both the United States and China come clean in owning the false narratives that are pushing them apart. At this point, my vision of engagement is an exercise in imagination, more as a starting point for discussion rather than a polished product. I welcome your feedback on how to sharpen the focus of this critical debate.

Next: The Case for Engagement

I hope you are correct on politics. I know you are right on the merits of people-to-people exchange.

Agree on your characterization of the arrogant hegemon. But would not hold China blameless either.