Feeling Liberated Yet?

Don't underestimate the perils of yet another Liberation Day!

For most of us, deadlines come and go. That’s especially the case in Trump 2.0. Whether you dub the outcome as TACO (Trump Always Chickens Out) or as a manifestation of the time-honored tendency of Washington to kick the proverbial can down the road, the implications are pretty much the same: political promises are made to be broken.

Liberation Day was a classic example — a big, beautiful bluff, to borrow the vernacular of America’s 47th president. The markets swooned for a week in the immediate aftermath of the shocking “reciprocal” tariff pronouncements of April 2, prompting the first of many TACO sidesteps. A subsequent “pause” allowed Trump to cobble together a few high-profile deals — notably with the EU and Japan but not with China, which apparently qualified for another 90-day kick of the can. The rest of America’s trading partners were politiely informed through a July 31 executive order of modified reciprocal tariff rates that generally fell in the 10% to 30% range (with a few outliers on the upside like Switzerland (39%), Syria (41%), Myanmar (40%), Laos (40%), and Iraq (35%)). The broad consensus of talking heads has been quick to conclude that this is Trump’s final word in his triumphant tariff war and that the worst is now over for the global trade cycle.

That is likely to be wishful thinking. Such a sanguine conclusion presumes that a couple of months of benign economic statistics on inflation and growth justify the feel-good verdict that the trade war is a nothing-burger. That all but dismisses the complex transmission mechanism from tariffs to pricing pass-through (largely to importers and US consumers) to shifts in import patterns, to the trade deficit — and eventually to GDP growth. It pays to remember that the sizable tariff hikes directed at China in 2018-19 took between three and four years to play out through those various channels — including an unmistakable diversion of trade flows away from China toward America’s other trading partners that pushed the overall trade deficit higher.

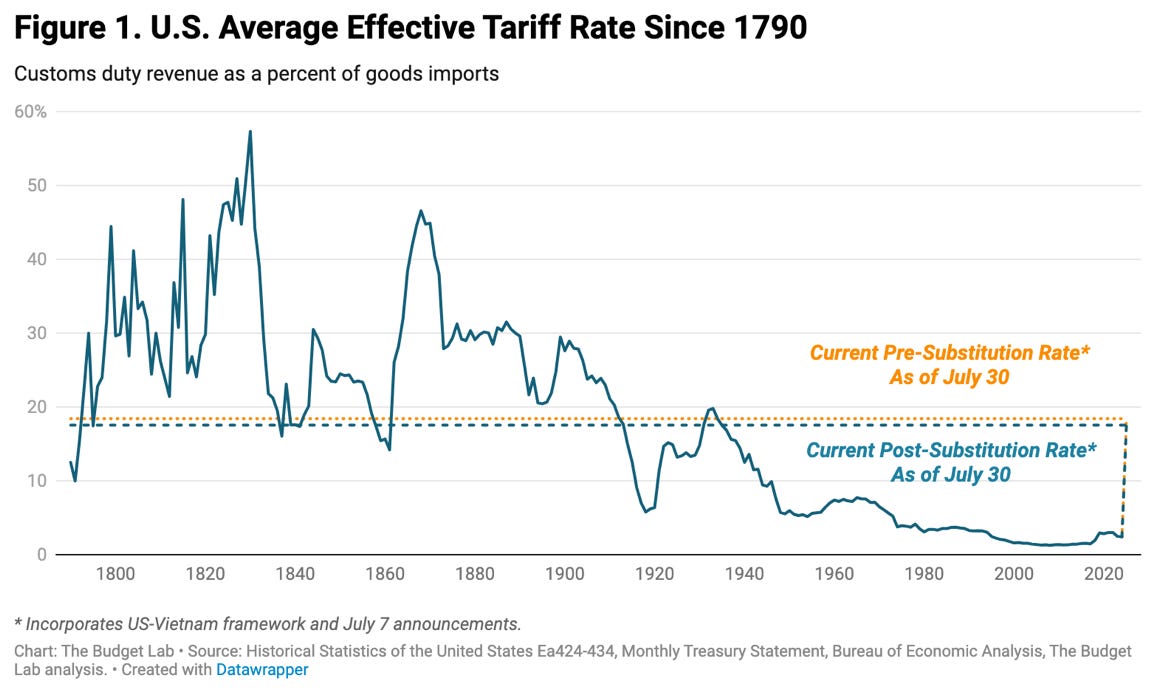

Of course, the current round of tariff hikes is very different from that of 2018-19 — it is both larger and broader. By Yale Budget Lab metrics, the US effective tariff rate soared to 18.4% by July 30 ( a figure that includes the 15% tariff rate negotiated with the EU on July 27 and a 25% rate on India but does not include the flurry of July 31 announcements that may push the average effective tariff rate slightly above the July 30 estimate). In any case, at 18.4%, the average tariff rate represents a 15.6 percentage point increase from the 2.8% reading over the previous five years (2020-24), fully eleven times the size of the 1.4 percentage point increase in overall effective tariffs that occurred in the aftermath of the earlier targeted strike against China. All this puts US tariffs at their highest rate since the Smoot Hawley days of 1933.

The Smoot Hawley comparison is especially notable for three reasons: First, it triggered a powerful wave of tit-for-tat retaliatory tariff hikes from America’s trading partners — a response that Trump is attempting to neutralize through his asymmetrical trade deals as evidenced by the weekend agreement with the EU. Second, global trade plunged by a little more than 60% in the aftermath of the 1930 enactment of the Smoot Hawley Trade Act — a key contributing factor to the worldwide Great Depression. Third, the US was already in a high-tariff regime when Smoot Hawley was enacted; over the 1931-34 period effective tariffs peaked at an average of 18.8% — “only” a five-percentage point increase from the average tariff rate of 13.8% over the prior ten years (1921-30). Significantly, relative to pre-Smoot Hawley norms, the current tariff hike hits a US import share of GDP that is nearly three times what it was back then, making it a far more serious shock than was the case in the early 1930s when global trade and the world economy were collapsing.

But the markets and much of the punditry have jumped to the conclusion that tariffs don't matter, in part, clinging to the nonsensical argument of President Trump that US tax coffers are swollen with newfound revenues from foreign countries. While there is no mistaking the surge in tariff revenues — now running at close to some $30 billion per month — the evidence is clear that the checks are being written by US importers. A key question remains as to how much of the tariff hike will eventually be passed through to American consumers, showing up as an increase in consumer prices. The June CPI report pointed to the first signs of just such an impact, and I suspect there will be more to come in the months ahead.

At the same time, GDP-based trade statistics for the first half of 2025 dispel the notion that tariffs don’t matter for the US economy. A front-loading of imports in the first quarter ahead of the expected tariff hikes was almost completely unwound in the second quarter; with imports having a negative sign in the GDP accounts, this had the seemingly perverse impact of reducing GDP growth in the first quarter and boosting growth in the second period. Unsurprisingly, quarter-to-quarter volatility was concentrated in the tariff-sensitive import categories of industrial materials, consumer products (ex autos and food), and motor vehicles. For these three categories, combined, inflation-adjusted imports, were down by nearly 15% (annualized) in 2Q2025 from year-end 2024 levels. Like I said, tariffs matter.

The deeper question pertains to the overall trade deficit, undoubtedly the most important metric in judging the overall impacts of a trade war. Key to the answer, and a subject that I have droned on about for longer than I care to remember, is the macroeconomic link between domestic saving and broad current account and multilateral trade deficits. Reflecting the big, not-so-beautiful budget deficits of Trump 2.0, there will be added pressure on an already rock-bottom net domestic saving rate — just 0.8% of national income in 1Q2025 (latest data) — undoubtedly leading to a further widening of the overall trade deficit. Not exactly the liberating breakthrough that Trump has promised US manufacturing companies and American workers.

The still unresolved China wildcard will only complicate the situation. When the dust settles — probably after another pause and a glitzy Xi-Trump summit — I still suspect that Chinese imports will be tariffed at a rate higher than that on other US trading partners. Like the case in the aftermath of the tariff hikes of 2018-19, for a saving-short US economy that will lead to trade diversion away from China — but this time, with the double whammy of shifts to other higher cost US trading partners who have been hit with liberating tariffs of their own. Yes, all this will take time to unfold, underscoring the likelihood of lagged impacts that myopic markets are ignoring.

Finally, there is an important judicial angle to all this that I have addressed earlier — the possibility that a Federal Appeals Court will uphold an earlier verdict of the US Court of International Trade that found reciprocal tariffs to be an unconstitutional application of the International Economic Emergency Powers Act. If this verdict holds — hearings are currently under way with a likely final appeal to the Supreme Court — then the United States, to say nothing of the rest of the world, might finally escape the wrath of Trump’s draconian trade policies. That would be a Liberation Day truly worth celebrating!