Consumption According to Xi

Priorities vs. analytics

A subtle shift can now be detected in the Chinese consumption story. President Xi Jinping is attempting to elevate the role of consumer-led rebalancing as a strategic goal of China’s upcoming development. This comes as a welcome development. Long the laggard in the Chinese growth miracle, promises of consumer-led growth have become tired and repetitive. Even recently, in the aftermath of the so-called Fourth Plenum of late October, consumption was still relegated to a third-order priority, behind industrial deepening (#1) and indigenous innovation (#2).

This focus appears to be changing. In a keynote speech to the just-concluded Central Economic Work Conference, Xi Jinping made an elliptical reference to a rethinking of this ranking, putting stronger emphasis on the “principle of prioritizing domestic demand.” This was, at least, a nod in the right direction. But it was still a very broad statement. Domestic demand can cover a wide range of activities, from business capital spending and residential construction to government purchases of goods and services and household consumption. I was hoping that Xi would focus more on the personal consumption piece of domestic demand, which the latest numbers (2024) show still stands at an anemic 39.9% of Chinese GDP.

A just-published article by Xi Jinping in the current issue of Qiushi, the Chinese Communist Party’s leading theoretical journal, sharpens this focus a bit. Entitled, “Expanding domestic demand is a strategic move,” the article essentially traces the evolution of Xi’s thinking on the Chinese consumer over the decade from 2015 to 2025. In doing so, it is aligned with many of the earlier ideologic considerations of Xi Jinping Thought — namely, the emphasis on the basic principles of supply-demand balance, demand-side buffers in a climate of unusual external shocks, the concept of dual circulation, the total factor productivity imperatives of supply-side structural reforms, and ultimately recognition of the central role of household consumption as the linchpin of China’s flourishing middle class.

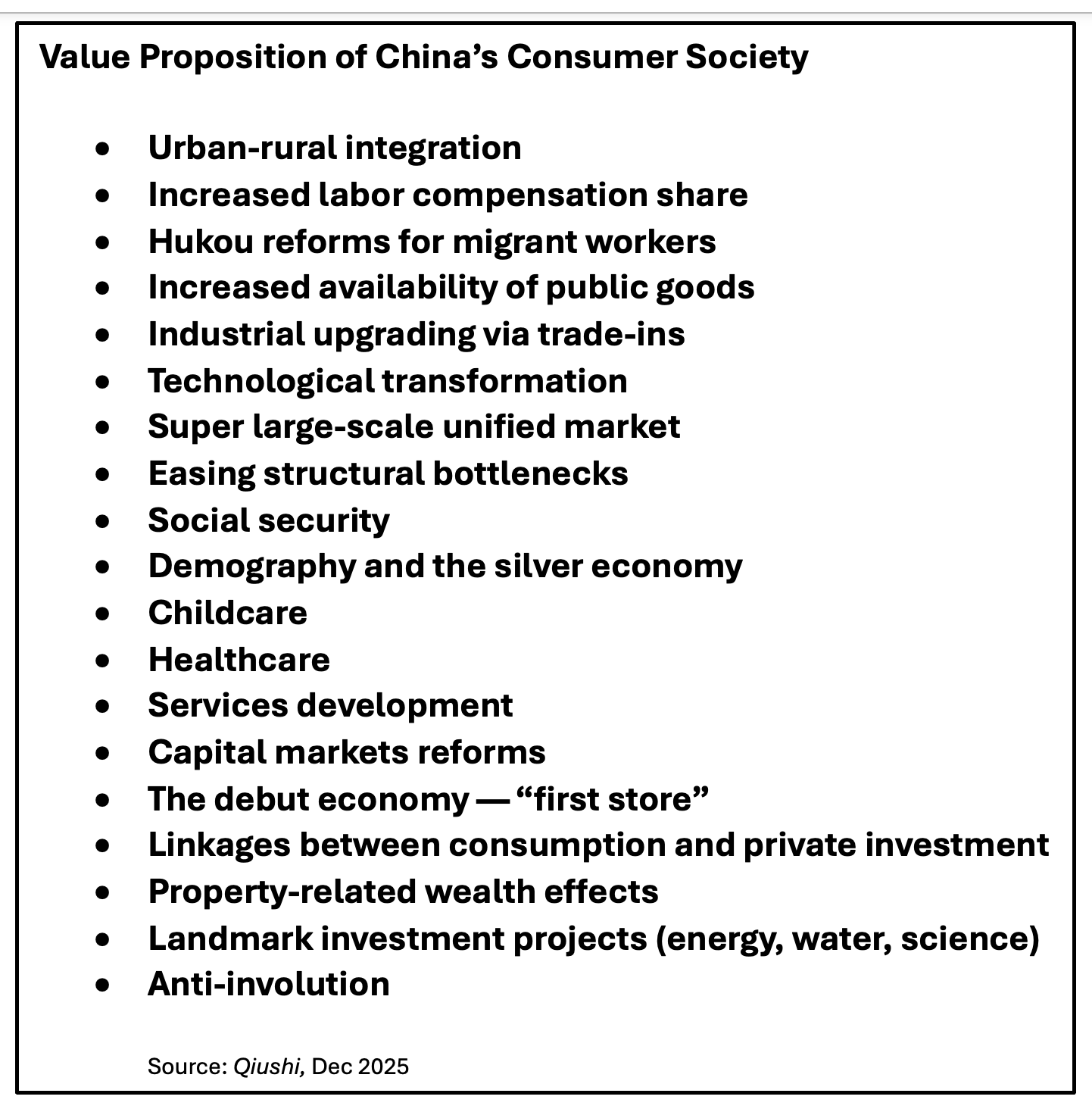

By labeling this effort a “strategic move,” Xi’s new Qiushi article is laudable as a demonstration of intent. In a companion Qiushi article (translated on Bill Bishop’s Sinocism), “Firmly Implementing the Strategy of Expanding Domestic Demand, “ top officials of the National Development and Reform Commission, China’s modern-day incarnation of the old State Planning Commission, attempt to flesh out this intent through a description of what can be dubbed the optimal characteristics of a modern Chinese consumer society; included are the following:

This is a comprehensive list to which any nation would aspire. Significantly, however, it is a broad collection of characteristics of an ideal consumer model, not an analytical framework that provides a convincing explanation of how China can get from Point A to Point B — from chronic underconsumption to a more normalized role for household demand in a flourishing consumer society. Instead, it borrows a page from the generic “wish-list approach” to Chinese reforms that we have become all too familiar with over the years — focusing more on the endgame rather than on the trajectory to the Promised Land. That’s been true of proposed reforms of market structures, state-owned enterprises, and capital markets — all of which are frequently depicted in terms of end-state goals rather than as a logical sequence of action-oriented building blocks.

It is largely for this reason that I have shifted my own approach as a long-standing advocate of Chinese consumer-led rebalancing. My preference now is for more of an ecumenical approach, allowing for a range of possibilities rather than a stylized solution to the problem. There are many consumer models in the economics literature, from income- and wealth-based to life cycle and permanent income theories. For China, my personal favorite has long addressed the excesses of precautionary saving, featuring social safety net reforms (i.e., pensions and healthcare) that are aimed at reducing the uncertainties and fears of a rapidly aging society. For what it’s worth, my views are broadly consistent with a new paper on Chinese saving reforms just published by the IMF research staff.

As an objective analyst, my purpose is not to push my own agenda. I recognize that the best solution for China may not be aligned with my personal preferences. As I have previously noted, it is, of course, China’s choice to figure all this out on its own terms. Easier said than done! Understanding the consumer culture is not an easy, or natural, thought process for the Chinese leadership. Long steeped in the producer models of central planning, Chinese leaders are outside their comfort zone when it comes to the behavioral models of personal decision making, especially consumption. Their preference for the unique “Chinese characteristics” of strategic decision making argues in favor of a more eclectic approach.

With that in mind, I now favor a different approach to Chinese consumer-led rebalancing — namely, thinking in terms of an explicit 2035 target for a 50% household consumption share of GDP, up ten percentage points from the newly released 2024 estimate of 39.9%. Such a targeting mechanism, in my view, is agnostic on the “correct” analytical solution to China’s consumption problem. Instead, it serves as an effective organizing mechanism for fitting various pieces of China’s consumption puzzle, and the alternative theories in which they are embedded, into a much broader macroeconomic structure.

Unfortunately, the latest efforts of Xi Jinping and the NDRC collectively fall short of that key objective. While they make a conceptual case for the glorious endgame of consumer-led rebalancing, they do not develop the empirically-based analytical building blocks required to execute this daunting transition. But progress often comes in small steps. For now, there is at least reason to be encouraged about an apparent shift in priorities in favor of consumer-led Chinese rebalancing. Yet in the end, it will take far more than priorities and intent to move the needle on the behavior of China’s 1.4 billion consumers. The focus needs to shift from intent to execution between now and the official release of the upcoming 15th Five-Year Plan in March 2026. Are the latest Qiushi articles a hint of that possibility? Stay tuned.