China's Rebalancing Imperative

Full paper prepared for — but not distributed to — the China Development Forum

Note: The following paper is an edited version of a longer invited submission to the Engagement Initiative of the 25th China Development Forum, held on March 24-24, 2024 in Beijing China. Unfortunately, as noted in an April 12 Project Syndicate article, “China Stifles Its Own Debate,” the paper was neither circulated to CDF attendees nor published for external distribution as was normally the case in the past.

China is facing a broad constellation of problems: an underperforming economy, a superpower conflict with the United States, stiff demographic headwinds, and a serious productivity challenge. Its policy response so far has drawn on a time-honored playbook that has proven successful in the past. But that may not be enough today. Battered from all sides, Chinese authorities need the courage and imagination to devise new solutions.

Despite being a diehard China optimist for 25 years, first as an investment banker and more recently as an academic, I have become far more cautious about the country’s medium- to longer-term economic outlook. This was not a spontaneous change in my thinking, but rather reflects my growing concern about the mismatch between powerful structural forces and China’s timeworn standard countercyclical toolkit.

This policy challenge highlights China’s need to shift from an export- and investment-led growth model to one driven increasingly by private consumption. In fact, I have repeatedly stressed China’s rebalancing imperative over the years, including in my Yale course “Next China,” my books Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China and, more recently, Accidental Conflict: America, China, and the Clash of False Narratives, and in a succession of presentations that I have made to the China Development Forum over many years.

The most successful development stories almost always involve major shifts in the sources of economic growth, which in turn allow economies to reinvent themselves out of necessity or by design. Failure to do so can lead to the so-called middle-income trap, which has ensnared most emerging economies since World War II. In China, the interplay of mounting external pressures, lagging household consumption, and falling productivity is driving a rebalancing imperative that will increasingly shape China’s policy choices in the years ahead.

The Slowdown Cometh

As a poor economy in the late 1970s, China was in desperate need of a new recipe for growth. The developed world, in the grip of wrenching stagflation, had come to a similar realization. Trade liberalization offered a mutually beneficial solution. In line with Deng Xiaoping’s strategy of “reform and opening-up,” China turned to external demand – especially from the United States – to generate strong export- and investment-led economic growth. China’s low-cost, increasingly higher-quality goods were a boon for income-constrained consumers in the West –an economic marriage of convenience that unleashed a powerful wave of globalization.

From the early 1980s until 2005, China was arguably the world’s greatest beneficiary of trade liberalization. But the 2008-09 global financial crisis reversed its role. China went from being a global “taker” – drawing on external demand to support its economy – to being a global “maker” – generating incremental output to support a world facing a profound shortfall of aggregate demand. Indeed, China’s strong economic growth was the only thing that prevented a fragile post-crisis world from slipping back into recession.

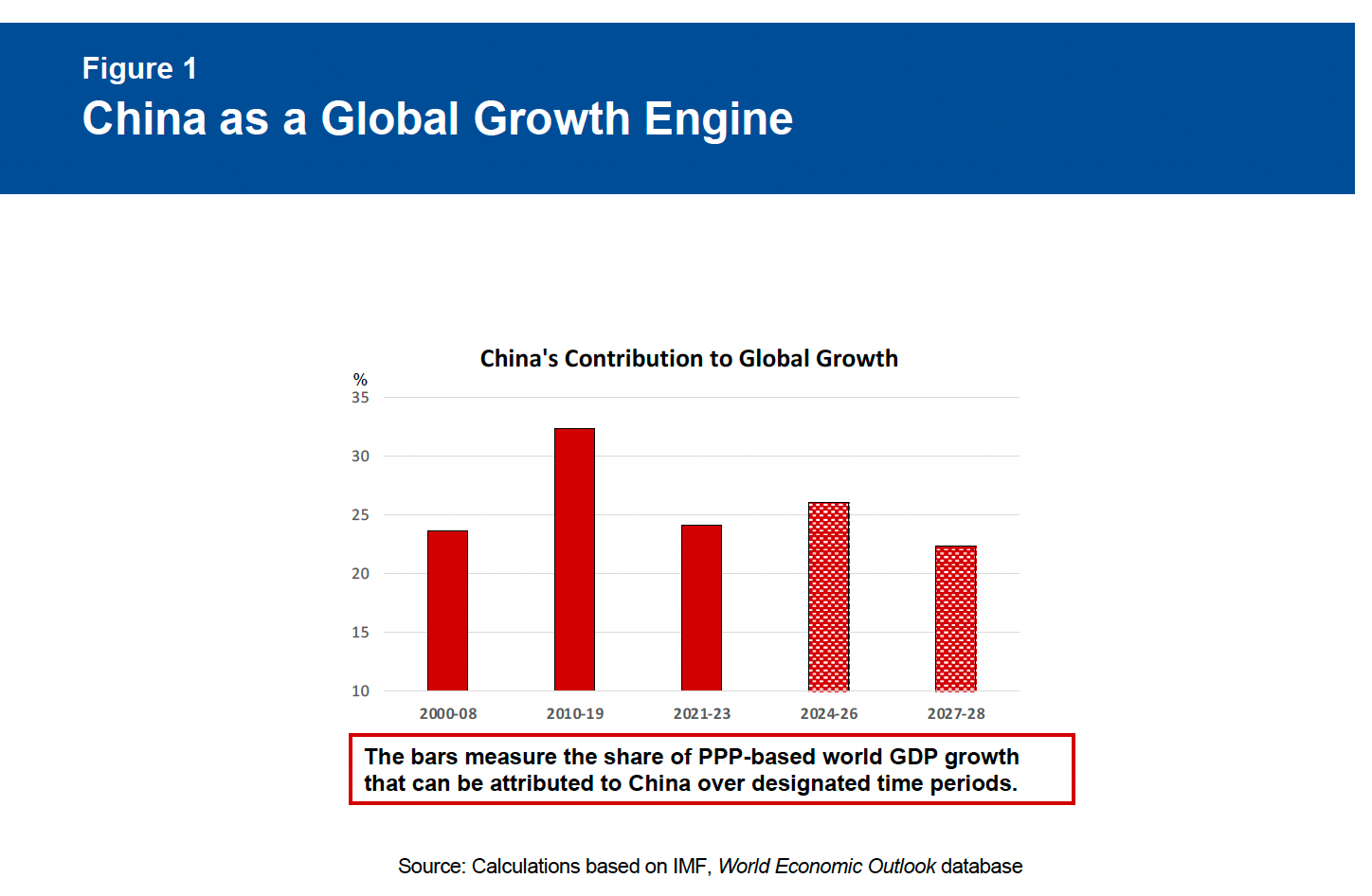

As a result of this role reversal, China deservedly earned a reputation as an engine of global economic growth, especially in the decade following the global financial crisis. As Figure 1 shows, China accounted for fully 32% of cumulative growth in world GDP from 2010 to 2019, compared to 24% from 2000 to 2008. China’s strong economic growth underpinned a sharp increase in China’s share of world GDP in purchasing-power-parity (PPP) terms, from 11.1% in 2007 to 17.2% in 2019.

But China is not the growth engine it used to be. China accounted for just 24% of the cumulative growth in world GDP from 2020 to 2023. While still impressive and much higher than any other country’s, China’s contribution to global growth has fallen to pre-2008 levels. This change reflects shrinking incremental gains in China’s share of world output in PPP terms and, more importantly, a slowdown inits rate of economic growth, from 7.7.% in 2010-19 to 5.5% in 2021-23.

This finding is at odds with the narratives that I have recently encountered in China. Chinese officials and local media still sing the praises of China as the main driver of global economic growth. While technically correct, the story is more nuanced. According to the International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook, China’s contribution to global growth will fall further, to around 22% by 2027-28. Yes, China remains the world’s major growth engine, but this is more a reflection of the Chinese economy’s size than of its underlying dynamism. The global growth engine fueled by the Chinese economy is slowing down.

There is, of course, another important dimension to all this: the US-China conflict. This month marks the sixth anniversary of the Sino-American trade war, which began in 2018 when former President Donald Trump introduced steep increases in US tariffs on Chinese imports. President Joe Biden’s [no link necessary] administration has largely maintained the Trump-era tariffs, while imposing additional sanctions through the so-called entity list and “de-risking,” with a focus on advanced technologies critical to national security.

As a result, the once seemingly open-ended efficiency dividends of outsourcing and offshoring production – an aspect of hyper-globalization that benefited China more than any other emerging market – have given way to a geopolitics-driven shift to “friend-shoring” that has diverted trade away from China. This partial decoupling has come as an especially rude awakening for China. What globalization giveth, deglobalization taketh away. Barring a miraculous breakthrough in the US-China conflict – highly unlikely in the run-up to November’s US presidential election – geopolitical factors will continue to put pressure on the Chinese economy.

Lastly, it is worth noting that the world economy is not nearly as strong as media reports suggest. With the US economy surprisingly strong, talk of a global soft landing is in the air. As Figure 2 shows, the global economy is projected to expand at a pace of 3.1% through 2028. Although seemingly strong on the surface, such a trajectory is not without risk.

That’s because a global growth rate of 3.1% is midway between the longer-term trend of about 3.5% and the 2.5% threshold normally associated with global recession. Amid downside risks to economic growth in both Europe and Japan, another major shock – hardly unimaginable, given the recent outbreak of two major wars and rising geostrategic tensions in Asia – could lower world economic growth to its stall speed.

If that happens, the global economy would lack any cushion, and another shock could easily tip the world into recession. As also shown in Figure 2, whenever world economic growth has fallen into the lower portion of the 2.5-3% zone, a global recession follows far more often than not. Needless to say, such an outcome would be especially problematic for China’s export-dependent growth model, which is already vulnerable to what Chinese authorities are calling “a complex and grave international environment.”

Given the multitude of headwinds that China is now facing, both at home and abroad, finding alternative sources of economic growth – what Chinese President Xi Jinping has called “a new pattern of development” – has become an urgent priority.

Unleashing Domestic Demand

This is hardly the first time that China has had to cope with negative global shocks. Starting with the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s and the dot-com recession of the early 2000s, and continuing through the global financial crisis of 2008-09 and the more recent Covid [note: I prefer this convention and have used it past PS articles] pandemic, China has developed a time-tested strategy: using traditional countercyclical policy tools, both fiscal and monetary, to sustain rapid GDP growth by stimulating domestic demand. While attending the China Development Forum in the early 2000s, I remember discussing possible external shocks with then Premier Zhu Rongji. His response – an investment-driven proactive fiscal stimulus – is still an important feature of China’s playbook.

But today, a major downturn in the Chinese property sector, amplified by a huge debt overhang, has eroded the potency of any investment offset, reducing considerably the possible benefits of countercyclical policies. That puts the focus squarely on the Chinese consumer.

It has long been obvious that household consumption as a share of the Chinese economy is far too low, as Figure 3 shows. The main culprit is the lack of a broad social safety net; provisions for retirement and health care are particularly inadequate. In the face of an uncertain future, aging Chinese consumers opt for fear-driven precautionary saving over discretionary consumption. Until this urgent challenge is addressed, under-consumption and excess saving will persist.

Moreover, China’s deeply troubled property market has added a new dimension to this dynamic, with falling home prices and reduced household wealth exacerbating the economic vulnerability that has held back private consumption. Taken together, these forces will continue to stymie Chinese rebalancing, an especially worrisome outcome for an economy in dire need of new sources of growth.

China’s lagging domestic consumption is at odds with the official government position on the state of the Chinese economy. According to the latest Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China, final consumption expenditure was estimated to have contributed 4.3 percentage points, or more than 80%, of last year’s 5.2% increase in total Chinese GDP – nearly three times the 1.5 percentage points contributed by gross capital formation.

These figures paint a surprisingly robust picture of consumption-led Chinese economic growth. The disparity with my depiction of Chinese under-consumption is largely technical, traceable to the United Nations System of National Accounts (SNA), the international standard for national income accounting.

The SNA measures final consumption as the sum of household consumption plus consumption of the “broader community” of businesses and government units. The latter two categories accounted for around 16 percentage points of Chinese GDP in 2022, according to the latest figures, which boosted SNA-based final consumption expenditure as a share of GDP to an estimated 53.2% in 2022, well above the 37.2% attributed to the household sector.

Consequently, when Chinese authorities boast about the newfound strength of consumption-led economic growth, it is important to understand that they are using a much broader metric of national consumption than I am. My focus is exclusively on household final consumption expenditure, a chronically weak segment of the Chinese economy that remains a prime candidate to drive the long overdue – and increasingly urgent – rebalancing.

While the arguments for consumer-led rebalancing are already well-established, the IMF’s latest Article IV consultation with China underscores this case. IMF researchers find that China’s household saving rate, roughly 33% in 2022, contrasts sharply with the median global household saving rate, which the Fund puts at around 12%. This likely reflects the pressure on asset prices – homes, yes, but also underwater equity holdings that are suffering through a wrenching three-year bear market.

At the same time, the IMF estimates that China spends only 8% of GDP on social protection, at the low end of comparable countries and half of what Japan spends. Accordingly, the IMF concludes that “measures to expand the social safety net, which would reduce the need for precautionary saving, are essential for rebalancing.” With geopolitical pressures mounting and the debt-stricken Chinese property market continuing to deflate, I couldn’t agree more.

Growth Prospects May Hinge on Productivity

But even if consumer-led rebalancing fails to materialize in the coming years, all is not lost. Such a scenario would bring the productivity-based solution to China’s growth dilemma into sharper focus. Economic theory is clear that maintaining steady GDP growth with fewer workers requires extracting more value-added from each one, meaning that accelerating productivity growth is all the more vital.

Productivity is as important for China’s market-based socialist system as it is for a capitalist economy. Economists have identified several prominent sources of productivity growth, including technology, investment in human capital, research and development, and inter-industry shifts in the mix of national output. The late Nobel laureate Robert Solow, the academic father of modern growth theory, put it best, framing productivity as a “residual” proxy for technological progress after accounting for the physical contributions to output made by labor and capital.

Paul Krugman brought Solow’s growth-accounting framework to life in a celebrated 1994 Foreign Affairs article that stressed the difference between “perspiration and inspiration” in driving economic development. In a prescient warning of the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, Krugman argued that the success of the fast-growing East Asian Tigers was ultimately unsustainable because it was based on the perspiration of “catch-up” growth achieved by building new capacity and bringing workers from low-productivity rural areas to higher-productivity cities. These economies, he concluded, failed to follow through on the inspirational genius imbedded in the Solow productivity residual.

Chinese authorities should heed these lessons as they contemplate how to improve productivity. China has arguably taken the concept of perspiration to an extreme, benefiting enormously from a development model built on rapid population growth, unprecedented urban migration, and massive investment in productive capacity and infrastructure.

But the limits to perspiration are increasingly apparent: the UN estimates that China’s working-age population peaked in 2015 and will decline by nearly 220 million by 2049. Moreover, China’s rate of urbanization is starting to flatten out as it approaches 70%, while its total investment as a share of GDP remains extraordinarily high, at more than 40%. Given these figures, one could conclude that China must now shift from perspiration to inspiration, underscoring the potentially decisive role of productivity in shaping the country’s growth prospects – especially if consumer-led rebalancing remains disappointing.

In fact, Chinese policymakers, mindful of the perils of a shortfall in productivity growth, have increasingly focused on the need to avoid a situation like Japan’s. Over the past several years, the Chinese government has pushed supply-side structural reforms to kill off unproductive “zombie” firms and boost the productivity of surviving firms, while also emphasizing a technology-led industrial upgrading of “strategic emerging industries.”

While achieving productivity-led growth is the aim of such efforts, Chinese policymakers are now framing it in a slightly different way – namely, Xi Jinping’s emphasis on “new productive forces” to drive higher-quality economic development. This has been billed by Chinese state media as “an innovation and development of Marxist theory of productive forces.” In late February, Xi identified new productive forces as those “fostered by revolutionary technological breakthroughs, innovative allocation of production factors, and deep transformation and upgrading of industries … with a significant increase in total factor productivity as the core indicator” (emphasis added).

No matter how it is framed, a focus on total factor productivity (TFP) growth is music to my ears. At last year’s China Development Forum, I highlighted the critical importance of China’s TFP conundrum – as Figure 4 shows, it is has been trending downward since 2011 – to the success or failure of structural rebalancing. This is mainly because research has shown that the slowdown of Japan’s TFP growth may well have held the key to that country’s succession of lost decades.

This trend will not be easy to reverse, especially with China’s economy now drawing more support from low-productivity state-owned enterprises, while the “animal spirits” of the higher-productivity private sector remains under intense regulatory pressure. But Xi is right to confront this problem head-on. TFP will be decisive for navigating China’s ultimate growth challenge: the transition from perspiration to inspiration.

China’s Policy Challenge

I have not come lightly to this more cautious perspective, and I have taken a fair amount of flak for it, especially from long-biased US politicians and their media consorts who, in years past, have been critical of my more upbeat views on Chinese growth. John Maynard Keynes is often credited (though incorrectly) with having the humility to say, “When the facts change, I change my mind.” There can be little doubt that the facts surrounding the Chinese economy have changed.

Up until recently, my Chinese friends have been more open to debating whether China’s structural problems – especially its debt, demographic shifts, and mounting deflation risks – are now starting to resemble those that long afflicted Japan. Given that Japan’s failure to address the structural and institutional underpinnings of a serious TFP problem was a key factor contributing to its protracted malaise, and that those same concerns resonate in China today, it is appropriate to ask if the Chinese economy might be ensnared in a similar trap. Moreover, reversing the downward trend in TFP aligns with both my proposed rebalancing framework and Xi’s recent policy comments.

In the end, this is not just an academic exercise. Describing a problem without taking a stab at a solution is an exercise in futility. In that spirit, I close with an assessment of the current Chinese policy strategy as seen through the lens of China’s rebalancing imperative, and offer three tentative conclusions:

First, the Chinese government needs a more enlightened policy response to its profound growth challenges. Its reliance on what it has long called “proactive fiscal stimulus and prudent monetary policy,” while necessary, is insufficient and too similar to the toolkit that China successfully deployed in the aftermath of past financial crises.

Chinese policymakers once again seem to be resorting to the brute force of large cash infusions to address major dislocations in the property market, local-government financing vehicles, and the stock market. But they may not be enough to offset powerful structural headwinds and advance the goal of economic rebalancing, which suggests that the risks to this year’s official growth target of around 5% are tilted to the downside.

Second, short-term countercyclical tactics do not effectively address the deeply rooted structural issues that are preventing China’s rebalancing. The combination of external pressures and lagging household consumption leaves China with no choice but to boost productivity to hit its medium- and longer-term growth objectives. Xi’s recent focus on the “new productive forces” of a “new development model,” and the productivity-enhancing supply-side initiatives that Premier Li Qiang announced in this year’s Government Work Report are encouraging.

But productivity challenges are especially daunting for China, give its recent TFP downtrend. The country’s economic leaders must therefore deepen their model-based assessments of the analytical and empirical linkages between Chinese policy design and its TFP quagmire.

Lastly, the time has come for Chinese authorities to reform the social safety net as a means of jump-starting consumer-led rebalancing. Enhancing social services currently ranks far too low, at number ten, on the list of “major tasks for 2024” in Premier Li’s recent Work Report. The emphasis needs to shift from a fixation on quantity – boosting enrollment in nationwide health-care and retirement plans – to improving the quality of welfare programs by increasing the benefits offered by these schemes. Only then can the fear-driven excess saving of an aging population be replaced by an increased propensity to spend.

Unfortunately, China’s latest policy initiatives, such as a “worry-free consumption” initiative and a consumer goods trade-in program, are vague and focused on the short term. These stimuli are unlikely to boost long-term household consumption growth to the extent needed to raise its extraordinarily low share of GDP. The road to rebalancing runs straight through the untapped potential of the Chinese consumer.

Mindful of the inspiration deficit that ultimately brought the East Asian growth miracle crashing down, Chinese policymakers must seize the moment. A deeply entrenched countercyclical policy mindset is misaligned with China’s structural challenges: mounting deflationary risks, exacerbated by the lethal interplay between a rapidly aging population and serious productivity problems. At the same time, the government must reyurn to its earlier efforts to promote the animal spirits of innovation. That means ending the recent barrage of regulations that have stifled the once-dynamic private sector and sapped business and worker confidence.

But China’s policy agenda cannot be framed in isolation. The country’s fate is inextricably linked to the rest of the world, which is equally dependent on China. The Sino-American conflict – so far a trade and tech war, but with the early rumblings of a new cold war – poses a major threat to China’s domestic policy goals. Conflict resolution must be a high priority for both superpowers, and requires a new trust-based architecture of engagement like the new US-China secretariat that I propose in Accidental Conflict.

Great countries are at their best when they rise to meet formidable challenges. That is very much the case for China today. A more expansive approach to economic stewardship is essential to muster the courage and regain the imaginative vision that underpinned reformers’ success in the past.

Dr Roach, thank you so much for sharing your excellent analysis of China’s economic prospects. It’s a pity the organizers of China Development Forum did not distribute your research paper. What you discussed are proposals for sound economic policy making that the Chinese leadership should have ears to listen to. It’s a pity the CDF did not share your excellent suggestions. I am a former financial journalist at Bloomberg and Institutional Investor who interviewed you on various occasions in the past. Thank you for inviting me to join your Substack readership.

You are a great scholar worthy of being remembered in history. The world will become more peaceful, prosperous and stable because of your long-term, correct and wise writings.

I am a Taiwanese. I am very worried about a war in Taiwan. I hope that if you have the opportunity, you can publish a book or article and tell us: If we don't change, when will war break out in Taiwan?