China Doubles Down

What does the Fourth Plenum have to say about the upcoming 15th Five Year Plan?

I am back in Shanghai for the first time in a few years. Full of character, China’s most cosmopolitan city offers something that the rest of the nation lacks — a vibrant consumer sector. Its per capita disposable income and spending are nearly double that of the rest of China.

I have long hoped that the Chinese leadership would promote the Shanghai consumer model as a template for the nation as a whole. Indeed, there have been hints that the government would use the upcoming 15th Five-Year Plan to implement a long-awaited strategic rebalancing toward consumer-led Chinese economic growth. The message from the just-completed Fourth Plenum of the CPC Central Committee says otherwise.

This meeting typically provides a strong signal of what to expect when the new plan is formally released at the upcoming Two Sessions meetings, which will next be held in March 2026. The full communiqué (released earlier today) leaves little doubt of the key priorities: first, deepening China’s industrial network; second, pushing further on indigenous innovation; and third, household consumption.

This is disappointing in the following sense: China’s technological prowess is so well assured at this point, it makes little sense to dwell on the obvious. The planning exercise should be put to better use in tackling the nation’s most dauting challenge — a long-awaited structural rebalancing. For that reason, alone, I was disappointed that consumer-led growth did not receive stronger emphasis in the message of the Fourth Plenum.

By no means am I suggesting that China should walk away from all that it has accomplished over the two plans of the past ten years, especially in terms of its advances in technology and innovation. Over that period, China has closed the innovations gap with the rest of the world, as per the metrics of the Global Innovations Index. And it now accounts for around 30% of global manufacturing output, approximately equal to the combined shares of the United States, Europe, and Japan.

These are spectacular accomplishments that China has every reason to be very proud of. But rather than double down on this recent record, I was hoping that the message of the Plenum would elevate the case for consumer-led growth. A number three ranking on the priority list does not achieve that objective. There was a modest nod in the direction of social safety net reforms — long my favorite policy option to reduce the excesses of fear-driven precautionary saving of ageing Chinese workers and families. As per a vague reference in the communique, this was mainly focused on “strengthening universal, basic, and safety-net livelihood programs” — not nearly enough to move the needle of the low household consumption share of Chinese GDP.

I was hoping, instead, that the CCP would be more direct in setting an explicit target for increasing the household consumption share of Chinese GDP. My recommended target: 50% by 2035, up ten full percentage points from the latest reading of around 40% (for 2023). This would be a tough, but doable objective for China. It would require consumption growth to be double that in the remainder of the Chinese economy over the 2030 to 2049 period.

I call this outcome “doable” for two reasons: One, growth in the non-consumption segments of the Chinese economy will be hobbled by the combination of persistent headwinds in several areas: the long-beleaguered property sector; once vibrant exports that will face protectionist pressures and a weak global trade cycle; and a fixed investment sector that is nearing its limit at 40% of Chinese GDP. Two, it will require significant pro-consumption stimulus actions — not just my favorite safety net reform actions but any one of another of other possibilities, including Hukou reform for migrant workers, increasing the retirement age, developing the “silver economy,” and, the government’s recent favorite, trade-in campaigns for consumer durable goods.

In the end, of course, the choice between pro-consumption policy options is up to the Chinese leadership. The same can be said for the broader strategic priorities of the upcoming 15th Five-Year Plan. Far be it for me, or for any other so-called China watcher, to prescribe a single remedy that resolves the many complex challenges and problems that a vast Chinese nation must confront.

The message of the Fourth Plenum falls short of what I was hoping for. By doubling down on what has been working exceptionally well over the past decade, it is more backward than forward looking. By focusing more on the supply side than on the demand side of the Chinese economy, it is staying in the comfort zone of a nation steeped in the legacy of central planning.

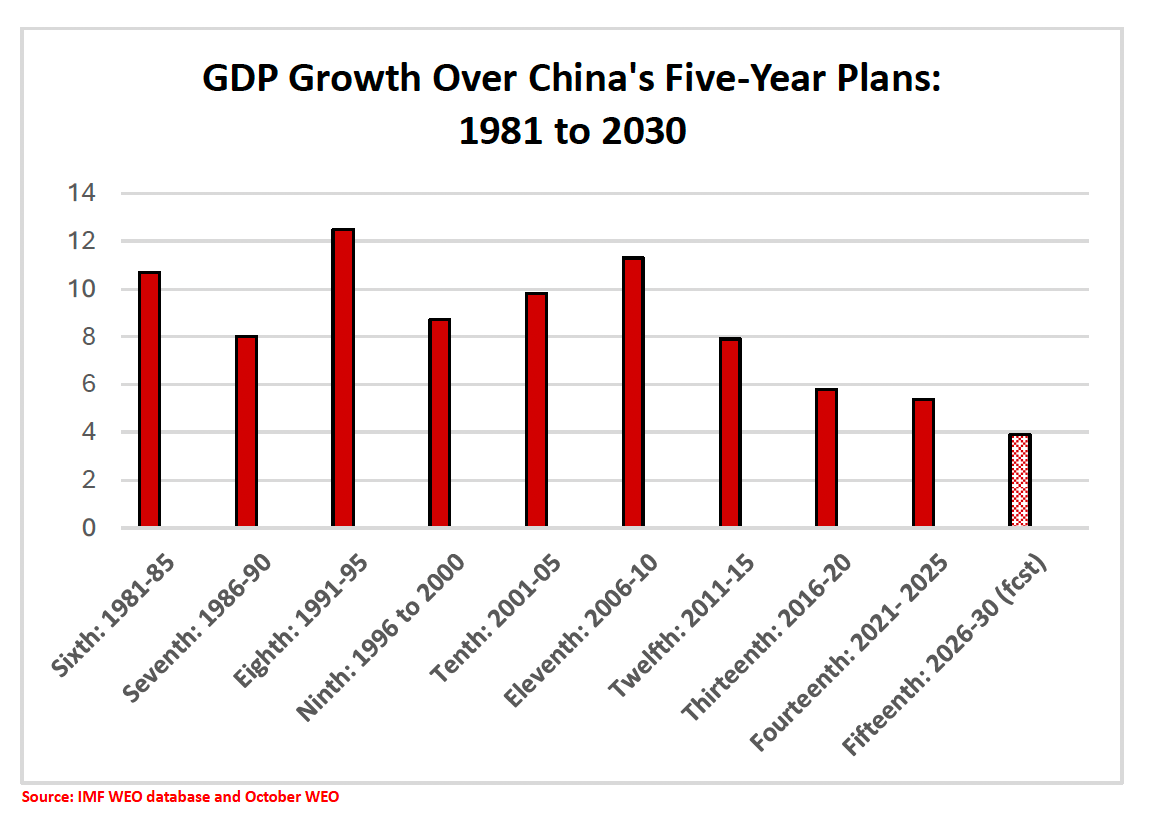

Every five years, the Chinese leadership has an extraordinary opportunity to change its strategy. China is in the midst of a profound slowdown in economic growth. As can be seen in the chart above, the five-year GDP growth rate, which peaked at 12.5% during the Eighth Five-Yer Plan (1991-95), is likely to be well less than half that in 2025 at 5.4% when the current 14th five-year plan draws to a close; moreover, according to the latest baseline forecast of the IMF, growth is likely to average just 3.9% over the five-year planning horizon of 2026 to 2030.

The 15th Five-Year Plan needs to be framed against this backdrop of a marked further slowing in Chinese economic growth. Can a plan which essentially doubles down on the same priorities — industrial upgrading and indigenous innovation — that have been in place during that slowdown, spontaneously generate a stronger growth outcome? There are still four months for the Chinese leadership to weigh these key considerations very carefully before finalizing their intentions for the next five years.

NOTE TO READERS: Due to Internet connectivity complications in China, the normal links to sources are missing in this post. That will be correcteed on my return to the US on Nov. 1.

Go with what’s been working or shift gears is always hard strategic decision and inertia is important.

However, what is different now is the Trump demolition of the global system. If China can’t count of consumers in the US and EU, Japan and Korea, and Australia the domestic consumption matters greatly.

Trump and his supporters and enablers have set the US on a dangerous path. While soybean farmers are selling ZERO product to China and going bankrupt, Kristy Noem is buying a pair of planes for $175 million for her travel and Trump is building an ostentatious ballroom. And for what? Parties and photo-ops?

When will the Congress, SCOTUS and MAGA wake up to what is going on and stop this madness? The list of Corporate America funding the ballroom and sucking up for tariff and tax breaks is against everything MAGA says they care about.

Frankly, the problems internal to China are about 113th on my list of problems the US has to deal with. America is anything but great right now unless you are a billionaire.

Deng Xiaoping lit an experimental fire circa 1980 that caught and spread. This largely explains the first set of growth figures. WTO accession combined with growing free trade and globalisation explains the next set. Double digit growth figures can’t last forever. The problems of growth at China’s scale are nearly unprecedented; one is constantly reminded whilst in China of the shear numbers of people. Many US cities are smaller than Chaoyang district in Beijing. Thus, “

As can be seen in the chart below, the five-year GDP growth rate, which peaked at 12.5% during the Eighth Five-Yer Plan (1991-95), is likely to be well less than half that in 2025 at 5.4% when the current 14th five-year plan draws to a close.”